Installationview “I Don't Expect Too Much” MISAKO&ROSEN TOKYO, 2019 Photo : Kei Okano

Installationview “I Don't Expect Too Much” MISAKO&ROSEN TOKYO, 2019 Photo : Kei Okano

Takashi Yasumura judged four straight New Cosmos of Photography contests, including the last ever 44th competition. He continues to take on new challenges in his work, informed by a consistent determination and a spirit of photographic exploration that constantly inspire him.

For this final issue of the New Cosmos of Photography interview , we spoke with him about his awareness of and approach to photography, which can be said to be central to his work. We also delved into some of the back stories to his work, ranging from Domestic Scandals, which was decorated with the Grand Prize in 1999, to his most recent work I don't expect too much.

The New Cosmos of Photography began in 1991 when I was in my sophomore year at university studying photography. Back then, the exhibitions were held once a year at P3 in Yotsuya — a space in the basement of a temple [Tocho-ji Temple]. I visited those exhibitions a number of times, and I saw firsthand how the New Cosmos of Photography exhibitions were gaining momentum with each passing year. I went along in those days just to look at the exhibits and I didn't enter any works. But I still think it had a big influence on me in making works. The New Cosmos of Photography magazine was also a big presence in my formative years. It was more than just a good reference when starting out in photography; it was a source of much inspiration — to see how many of the award winners were carving out their own places with their works. And it was good to be able to read the words of the award winners. I could get a sense of each artist's passion.

I think the scene was far too diverse to be reduced to a “girly photographers” movement. I did witness the “my life, my everyday” style that many photographers adopted. But I realized that wasn't me, even if only as a pretense. I was interested in using photography in a much different way. I believed strongly that if I were going to use photographs, I wanted to do something that could only be done with photographs.

I got the Honorable Mention for A Lukewarm Wind Blows, which was a series of photos of the place where I grew up. Domestic Scandals was an extension of that. Although both series have some similarities, what I paid attention to during their production was very different. For A Lukewarm Wind Blows, I tried to shoot the subjects to look as natural as possible, without dressing them up in any way. Whereas for Domestic Scandals, I was more conscious of putting affectation into the work.

“A Lukewarm Wind Blows” A Dog,1998

“Domestic Scandals” Japanese Oranges, 2002

Yes, it was. There's a belief that photography frees food or tools or whatever from their appointed roles in the world and allows you to glimpse them in a state you might call “the things as themselves”. Taking its cue from these slightly affected or exaggerated poses, the work tried to instill in the viewer's mind the true nature of the everyday in such a way that it would turn the ordinary, which is normally hard to be conscious of, into the ordinary.

It was a photo of a speaker. There was a large speaker placed in a corner made from fake wood-grain paneling. The woofer looked like the belly of an insect, and the other parts seemed to be “paying attention” because they were facing in the same direction. It looked totally bizarre to me. I think the grain of the fake paneling in the background and the details in the pink carpet had an impact too. When I looked at the scene through the viewfinder, I was blown away by the imposing nature of it all. I clearly remember even today how something inside me changed in that moment.

From that time on, I took far more care in choosing objects and backgrounds. I paid attention to how to arrange them to give the scene a slightly affected air. I would experiment with poses that brought out more of the essence of the subject. Contrived is the antonym of natural, but what I was seeking were scenes that left the viewer in doubt: Is this contrived or is this natural? What I noticed in taking photos of the speaker was that it was impossible to tell from the photos alone whether they depicted the speaker as it really was or whether they had been manipulated in some way. This got me thinking about whether something interesting would happen if I more consciously made use of such affectation. This train of thought was the start of the Domestic Scandals series.

I use a 4 x 5 camera not just because of how attractive the camera renders images and the materiality of the large photos. It's more to do with being able to compose the subject in the shot while viewing a large image. The size of the viewfinder is important to really see and capture your subject. Photography for me is the process of replacing a familiar object with a photo and then seeing it in a photo. That's why when I'm shooting I want to see and confirm the subject in a state as close as possible to the final photo.

“Domestic Scandals” A Shortcake, 2002

“Domestic Scandals” A Loudspeaker, 1998

“A Lukewarm Wind Blows” A Farmer, 1998

“A Lukewarm Wind Blows” Tori-niwa,1995

I didn't imagine I could win the Grand Prize, so I hadn't prepared anything for a solo exhibition. I remember being in a panic because it was a daunting task for me to come up with something in the year after winning the award. The concept for Nature Tracing didn't come together until about six months before the exhibition. I have memories of rushing around to get my driver's license because I figured I needed a car to go out and shoot. The idea behind the series was to use photography to contemplate the interactions and mutual influences between viewing actual scenes of nature and viewing painted or imitated nature.

That's right. I set out in my car with a learner's sticker on it, scared to death. [laughs] I took photos of real nature — so-called famous spots — and of imitated nature and contrasted the two. The work was a bit theoretical: it was like the words preceded the images. But I didn't have much time, so the actual production process was to first collect as many photos as possible with some connection to natural scenery. Then I composed the series while thinking of how best to combine all of these shots. I thought I had more than enough material to work with. But thanks to this excess, something eventually emerged that was comic or humorous. That's the kind of series it is, I think.

There hasn't been anything I'd call a significant change. But there have been more opportunities for people to see my work, so perhaps I have a stronger awareness that I should view my own work more objectively.

“Nature Tracing” A Squirrel, 2001

“Nature Tracing” Aso, 2003

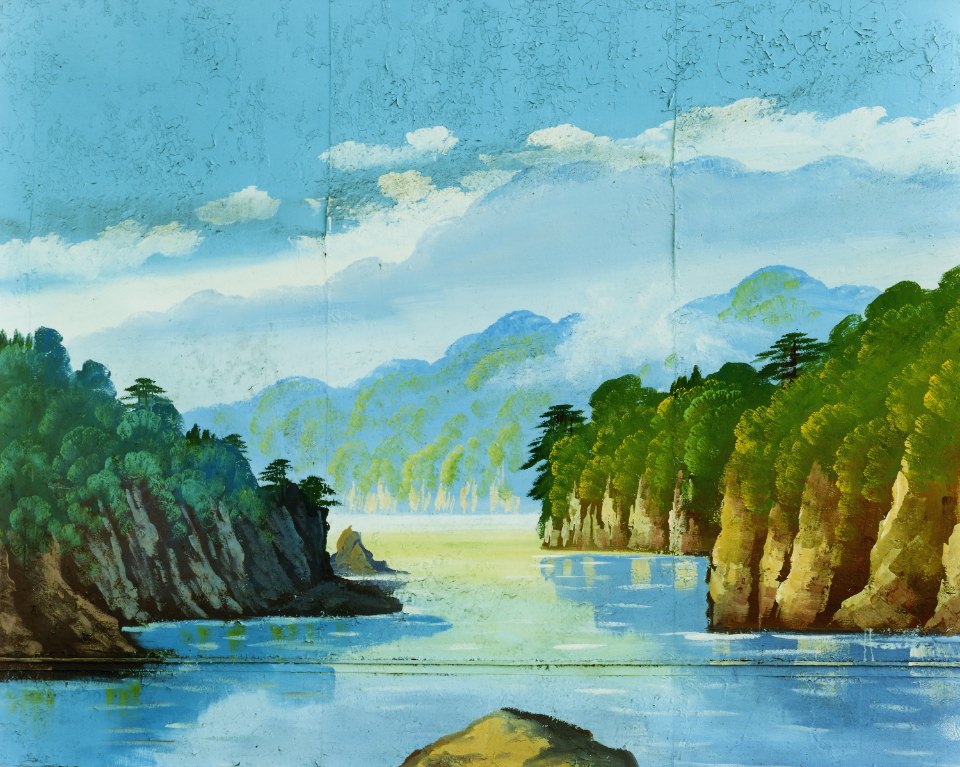

“Nature Tracing” Wall Painting in a Public Bathhouse(River), 2000

In contrast to Nature Tracing, a series about landscapes, If This Is A Planet is a series about being awestruck and overwhelmed by the sheer scale of nature, which can't be conveyed in the word “landscape”.

I asked people I encountered in the locations to walk slowly while I photographed them. I also took a number of shots with figures placed on the photos. So at first glance, it looks like there are people in the desolate setting. But if you look closely, you can tell these are figures placed on top of the photos. If you interpret the images as “nature versus people”, then you might have the sensation of stepping into a miniature world. On the other hand, you can interpret the images as “relationships between objects” — that is to say, having the figure as an object placed on the photo as an object. Putting the photos together in this way is meant to encourage the viewer to take a step back and gaze at the photos, instead of just peering into the portrayed worlds. Doing so might make the viewer suspicious about even the photos with real people in the scenes. Such doubts may lead viewers to ask themselves “what am I really looking at?” as well as make them aware of their own ingrained and unconscious patterns of viewing photography. To me, this way of looking at photography — the approach of looking at things from a bird's eye view — is akin to the approach of looking at this place as a planet, which is the theme of the work.

“If This Is a Planet” Yamaguchi(Akiyosidai), 2003

“If This Is a Planet” Akita(Yunuma), 2007

As I walked around volcanic areas and coastlines in various parts of Japan, I could sense the curvature of our planet earth. This sensation reminded me that the place I'm standing in right now is a planet. I also took photos of stars and other astronomical objects since they are the farthest objects we can see from earth. This is called astrophotography. I used a special motor drive for astrophotography called an equatorial mount. I think the title, If This Is A Planet, neatly sums up the work. There are many events in the world that are beyond human intelligence and human agency. But it's only when we encounter such events that the realization we are standing on a planet, and just how tiny we humans are, guides us to some kind of other, larger world. In this sense, I regard If This Is A Planet as a statement of proactive acceptance.

Once I get started on something, I get obsessed with it. I feel like I have to accomplish something while I'm alive.

“If This Is a Planet” Wakayama(Stars), 2006

“If This Is a Planet” A Figure(Man), 2011

It took from 2008 to 2015. Most of the photos are of public buildings and facilities in different parts of Japan.

Hokkaido in the north, Kyushu and Kagoshima in the south. I went to a lot of public spaces like community centers, parks, and ports. It felt like I was following a map like a door-to-door salesman.

Hmmm. Definitely it was the first time I was so captivated by color. But that alone wasn't enough to bring the work to life.

I admit it: it's all just walls and floors. [laughs]

The title 1/1 (one-to-one) came about through a bit of a complicated process. This fraction is a scale notation. On replicas or other things, 1/1 means the object is the actual size of the original. This doesn't mean that I printed the photos at the same size as the original objects. Rather, the conversation about what things are the same size goes back to when I was shooting.

As before, I used a 4 x 5 camera for this series. The camera was fixed on a tripod, and because the viewfinder is relatively large, I could easily compare by eye the image in the viewfinder with the subject while I shot. One time while I was doing this, the viewfinder image happened to appear like it was superimposed over the object in front of the camera. When shooting more complex objects, the viewfinder image would always seem reduced in some way compared to the actual object. But if I limited myself to simple elements like colored surfaces or lines, like the objects in this series, the image in the viewfinder would look identical to the real object. This gave the sensation that the viewfinder image was pasted on the real thing. That's when the expression 1/1 popped up in my mind as the notation to indicate something at actual size.

“1/1” Coca-Cola Red, July 13, 2012, Iwanai, Hokkaido

“1/1” Rainbow, December 22, 2015, Genkai, Saga

Many people have told me they are drawn to the graphical aspects of the photos. But that's not where my interest is. In making the series, I set a rule to avoid including any kind of obvious “background” in the photos. I filled the entire frame with what is presumably the subject in order to not have anything that could be called a “background”.

I'm especially interested in the backgrounds of photos. In a painting, for example, we know for certain that the artist placed paint in the background. But areas seen as backgrounds in photos sometimes look like the camera captured them on its own, or that maybe the photographer just didn't see them. Nevertheless, the background gets captured even if the photographer doesn't notice it. This, to me, makes backgrounds seem like areas devoid of human agency.

In that sense, the background could be called the most photographic part of a photo. I wondered what would a photo look like if I completely eliminated the “background” parts — the parts that account for most of the photographic character of a photo. And what would you feel looking at such a photo? So the point of the series was to probe these questions. The exhibited prints were as large as 120 x 150 cm. It's amazing how the details stand out when you look at the actual prints.

Ordinarily the materiality of things is enclosed in a container — whether that be a building or playground equipment. But by eliminating the background and losing the outline of the specific container, the materiality reveals itself with tremendous force. It's like experiencing the “raw” materiality of something.

No. In the production process, I actually feel I'm very wasteful. But I do try not to let waste just go to waste.

“1/1” Mizushima International Bowling Hall, August 19, 2008, Kurashiki, Okayama

I'm not that particular about film to be honest. I found the judging to be very fascinating. Especially the videos, as I have been shooting videos myself recently. Adding video capabilities to SLRs has given the option of shooting videos to people like me who have only taken photos before. I regard the emergence of video works to be a positive development. Especially those that don't fit in any existing category and give us images we have never seen before. I don't know whether it will remain a niche, but video is very inspiring.

The title in Japanese is read as “Waza Waza”. The work came about as I continued my theme of “seeing in photos”. I realized I had been photographing things I see with my eyes in order to see them in photos. That led me to want to see photos that have no meaning other than being photos. The more I dwelled on “being photos” and “seeing in photos”, the stronger my desire to try seeing the photo itself, which in itself is nothing. Since it's impossible to see a photo that captures nothing, we are forced to shoot something. In doing this, if what the inhuman eye of the lens captures arrives as honest amazement and a fresh experience, then I can hope to eventually get a sense of the photo itself.

Being able to come face-to-face with photographs that you think are truly astonishing. The joy that photography gives me always exceeds my imagination. Many times I have encountered something absolutely wonderful and I'm certain I have captured it in a brilliant photo. I go on to develop the shot with that excitement still fresh in my mind, only to be disappointed by the finished photo. Still, I feel even that premature joy opens up important places in my heart and mind. That, I believe, is what makes photography so interesting.

“I Don't Expect Too Much” Leafs, 2019

Absolutely. What's most interesting to me — what makes me positively euphoric — is printing a photo and looking it. Then as you react to the photo on an emotional level, you get this feeling of having the words to describe it on the tip of your tongue. It's that itchy feeling that the right words are just about to emerge, but never do. This is where I feel joy when looking at a photo — of course, this isn't limited to just photography. Your heart races as you strive to put your emotions into words, but the words don't come. It's as if the work is trying to expand the limits of what you know and understand; the sensation that the work has, by its own accord, accessed your latent memories and emotions and is attempting to unearth something there.

I think it's almost impossible to convey something through photography. Photos like mine are pretty obvious about what they capture. But as soon as you look for meaning in a particular photo, the photo becomes ambiguous and you can interpret it any way you like. The meaning of a photo and why it was taken are hard to tell from just the photo itself. This is why I put together multiple photos and create a visual context for them, which lends meaning to them. Maybe it's not something as definitive as meaning, but that's how I try to arrange photos into a work.

With photos, no matter how long you wait, the next instant never appears. With videos, you are held in constant state of not knowing what will happen next. If you don't continue watching, you won't know what the next moment will bring. It's like you are transfixed, in a state close to joy but intermingled with expectation and anticipation.

Technically speaking, a video is composed of 30 photos a second. This means a video is a sequence of photos that are constantly being swapped and replaced. Videos are closely related to photographs. But the sensations when looking at the two media are completely different. It's an odd thing.

“I Don't Expect Too Much” A Good Friend, 2017

“I Don't Expect Too Much” My Sock, 2017

If I have to try to define it, I'd liken it to another reality, another entity, that is constantly shaking and disturbing the real world. I realize that's a totally vague answer.

Winning an award at the New Cosmos of Photography was a huge event for me. I don't want to exaggerate, but it was a milestone that changed my life. I will be forever grateful for that.

I believe an artist's first work is very important. It's very likely that the works that earned an award at the New Cosmos of Photography were debut works. Your first work should be a work that carves out your place, in order for an unknown artist to become known. Your next work, of course, needs to top your first, but your first work will be with you your whole life. You can't choose your final work, but you do have the time and opportunity to carefully scrutinize your first.

“I Don't Expect Too Much” Falls, 2018

| 1972 | Born in Shiga Prefecture |

| 1995 | Graduated from the Department of Photography at the College of Art, Nihon University |

| 1999 | Won the Grand Prize at the 8th New Cosmos of Photography |

| 2005 | Published the photo collection Domestic Scandals; held the Takashi Yasumura Photo Exhibition at the Parco Museum |

| 2006 | Exhibited at the group exhibition Photo espana in Madrid |

| 2017 | Published the photo collection 1/1 |