What birds tell us Vol.1

Why are birds a conservation indicator?

Birds are often used as a conservation indicator. Why is that? Put simply, it is because most birds (with the exception of owl species) are active during the day and are easily observed by humans. Moreover, there are many vividly colorful birds, such as pheasants, peafowls, and Mandarin Ducks, which excite our eyes, and also birds such as Red-crowned Cranes and swans that have attracted people's attention throughout the ages for their beautifully clean white coloring. Small birds such as the Japanese Bush Warbler and the Japanese Robin have beautiful singing voices, while the Blue-and-white Flycatcher and the Narcissus Flycatcher are both beautiful to look at and to listen to. For these reasons, birds have from long ago been the subject of songs and paintings, and naturally attracted the interest of humans.

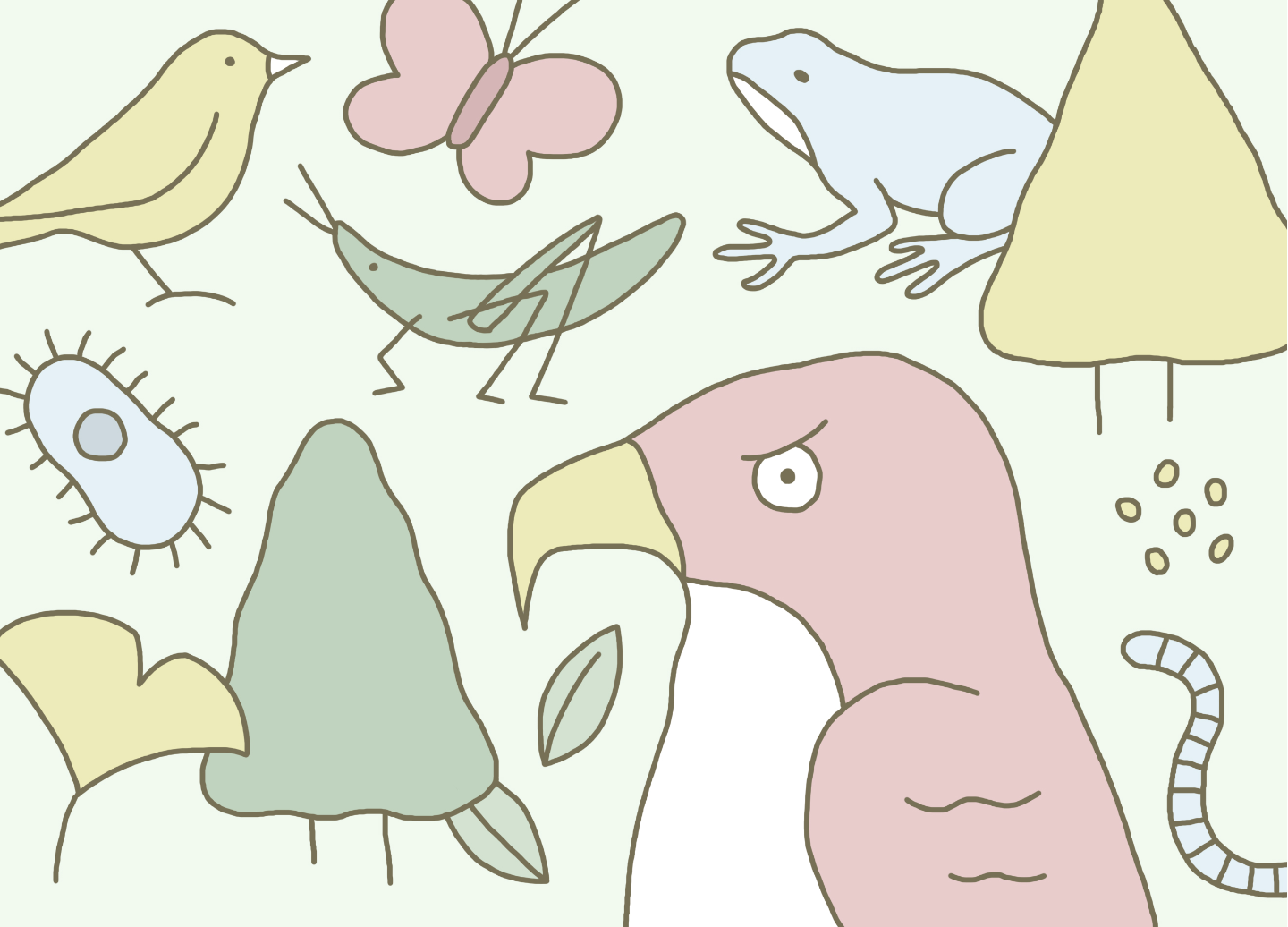

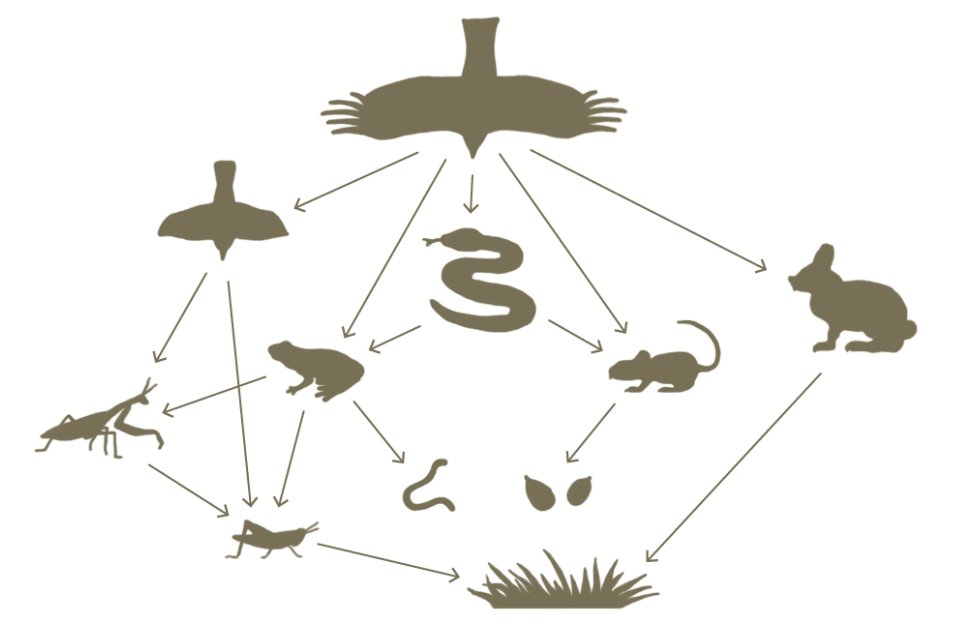

The importance of birds in the natural world, however, is not simply an emotional connection. When we consider the food chain in nature, birds, which have a diverse diet that includes insects, plants, seeds, fruits and also meat, are principal members of every level (trophic level) of the ecological pyramid. The health and functionality of an ecosystem can be determined by looking at the breadth of each level of the pyramid and whether there are several levels of the pyramid. At the top of the pyramid are carnivorous birds, called raptors or “birds of prey,” which include goshawks and owls.

Why are birds, not fur-bearing animals at the top of the ecological pyramid? There are of course large mammals such as deer, monkeys, and bears living in the forests of Japan. They are large in size and they appear to be living in thriving mountain wilderness areas. Yet, deer, monkeys, and bears are not apex predators in the food chain. That is because deer eat plants, and bears and wild boars have an omnivorous diet that consists heavily of plants.

The natural food chain describes the network relationship of “eat or be eaten” in the wild. Nutrients (or energy) produced by plants through photosynthesis, the process of turning water and carbon dioxide into glucose using the energy from sunlight, are consumed by herbivorous animals and carnivorous animals to sustain life, and then return to the earth. The animals at the top of the ecosystem are carnivorous animals.

In most places on our planet, large carnivorous animals are at the top of regional ecosystems. In the African savannah it is feline animals such as lions and cheetahs, in the jungles of India it is tigers, and in the plains of Siberia it is wolves that are the apex predators. How about in Japan? If Japanese wolves still roamed the land, we would likely say that it is the apex predator of the forest ecosystem in Japan. However, the Japanese wolf became extinct in the Meiji period, a Japanese era that extended from 1868 to 1912, and now there are no carnivorous animals that actively hunt deer and rabbits.

Taking over from the wolf as the apex predator of Japan's forest ecosystem are large raptors such as the Golden Eagle, Mountain Hawk-eagle, and Northern Goshawk. Among raptors the Golden Eagle reigns as king, and as a formidable hunter that can easily pick off a Japanese hare, Copper Pheasant, or even prey as large as a fawn, it holds the position of the ultimate apex predator.

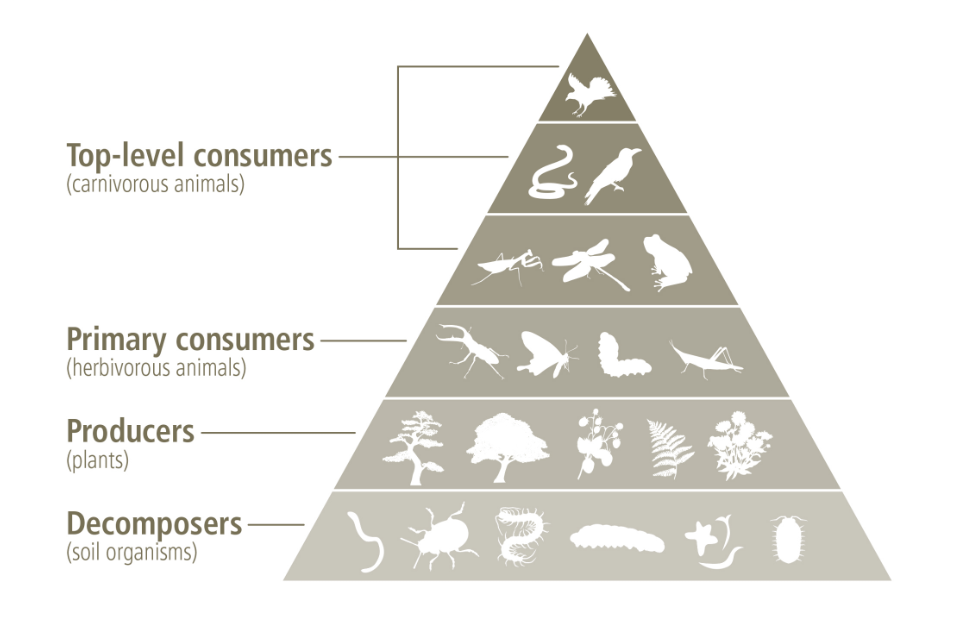

Since most people are not so familiar with forests where Golden Eagles or Mountain Hawk-eagles live, imagine Satoyama, undeveloped woodland near populated area, such as forested areas in the Kanto region. In the low mountain valleys, you will find rice paddy fields dotted throughout the valleys as well as broad-leaved deciduous forests containing konara oak, sawtooth oak and wild cherry trees. In winter, these trees lose all of their leaves, letting the light shine into the forest, and just as the green shoots of spring make their appearance, you can see from a distance the soft pink of the cherry blossoms intermittently dispersed across the landscape as though the forest was painted in soft pastel tones. And, the important thing to note in Satoyama is the evidence of human impact; people have reaped the bounty of the forest for the human dwellings that stand just outside of it. What then does the food chain of this forest look like?

The apex predator of Satoyama in the Kanto region is the Northern Goshawk. Its prey ranges from small birds like the Japanese Tit and sparrow to larger birds such as pheasants, and occasionally includes hares. Next to the Northern Goshawk, the Sparrowhawk reigns supreme as an expert small-bird hunter in slightly higher mountain elevations. The Common Buzzard hunts small creatures such as mice and snakes in more remote mountain areas. The main predator in Satoyama, the Grey-faced Buzzard-eagle, whose diet consists mainly of frogs and small snakes, is a long-time resident of the valley paddy fields. These predators occupy the top rung of the food chain in Satoyama.

What would happen if these birds disappeared? Nowadays deer have become too populous and the effect is the destruction of forest and agricultural produce in different areas. When one species experiences prolific growth when the animal that controls its population numbers disappears, it is often regarded as a pest or nuisance. When numbers of birds that prey on destructive insects, such as the Japanese Tit, declined for some time after the Second World War in Japan, insects such as the Fall Webworm Moth and the Gypsy Moth suddenly increased in large cities, and there was a period when trees lining the streets were completely naked of leaves. Now the trees lining city streets are mostly free of these destructive pests, and birds such as the Japanese Tit, the Brown-eared Bulbul, and the Japanese White-eye can often be seen in city parks.

The presence of these birds in park areas indicates a balanced ecosystem, one in which the various insects (this of course includes destructive insects, and other natural predators such as bees and spiders) and nuts that serve as food for birds are kept at an appropriate level, with no one species becoming more prevalent in the park's ecosystem and thus upsetting the balance. This also indicates that our living spaces are rich with nature and secure. So, this is why birds are said to be a conservation indicator.

Wildlife ecologist

Professor Emeritus, College of Science at Department of Life Science in Rikkyo University

Former President of the Ornithological Society of Japan

Born in 1950 in Osaka Prefecture. Areas of research include evolutionary ecology of plants and animals with particular focus on avian species, and also environmental issues. Vice-president and Trustee member of the Wild Bird Society of Japan. Currently works as editor in chief of Strix, a member-authored journal of field ornithology, published by the Wild Bird Society of Japan.