What birds tell us Vol.4

Birds that create acorn forests

Plants disperse seed and propagate though various methods, such as being eaten by birds or being carried by the wind. That is not only the process for regenerating the forest (the forest is renewed while plants such as grasses and trees grow and natural selection between plant species occurs) but it also influences the structure of the ecosystem as well. Moreover, it is also a very important mechanism and function to maintain diversity.

Besides plants that invite the attention of birds by producing delicious-looking fruit, such as red fruit or black fruit, there are also plants that disperse their seed by making use of the hoarding behavior of birds and other animals.

The fruit of oak species, including Japanese blue oak, white oak, chinquapin, and Mongolian oak, is commonly called an acorn. When you split open an acorn and look at the structure inside, you can see that the seed is enclosed in a thin seed coat, and borne in a hard shell.

The acorn though is too heavy to be carried by the wind, and there is no tantalizing reward for a bird's efforts to carry it in the form of a flesh it can eat. Of course it is possible that an acorn could fall off a tree naturally and be carried along by water, but it would be a one-way dispersion, travelling from a high place to a low place, from a mountain down to a flat area. Despite this, why is it that oak trees in the mountains continue to live on? It is because birds and other animals help to disperse acorns.

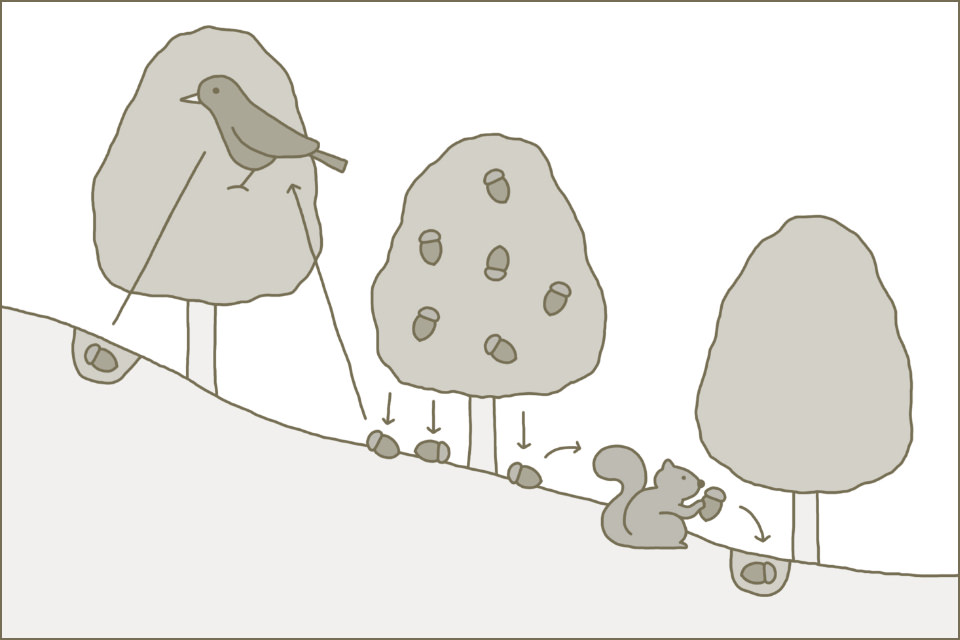

Squirrels, mice, and Eurasian Jays transport acorns. On the island of Honshu it is Japanese squirrels, Eurasian Jays, and large Japanese field mice, and on Hokkaido it is Hokkaido squirrels, chipmunks, Subspecies of Eurasian Jay, and large Japanese field mice that are responsible for dispersing acorns. Squirrels separate and store caches of one or more acorns in the ground around the base of a tree or in a hollow of a tree. Chipmunks and field mice fill their deep winter burrow with acorns, and shallowly bury excess acorns in the ground. Eurasian Jays bury acorns in the ground one at a time and cover each one with dead leaves.

Squirrels, field mice, and Eurasian Jays eat the stored acorns over the winter as their main food source. But, not all of the acorns they have stored get eaten. There are likely Eurasian Jays that have a poor memory, and there are also mice that fall victim to owls. So some of the buried acorns remain in the ground uneaten.

And, since acorns are vulnerable to dryness, those that just fall to the ground without being picked up and stored by animals lose their ability to germinate after one week. Even if an acorn germinates sometime in autumn, if it just lies on the ground it will die without the roots being able to penetrate the ground. Only acorns that have been shallowly buried in the ground by birds or other animals will be able to sprout. This is how acorn forests are renewed. Eurasian Jays also probably carry acorns up to the top of a mountain from the base. Acorn groves will not disappear from mountains because there are birds and other animals that store up acorn seeds.

Since the acorns of many species of Castanopsis (chinquapin), including Castanopsis sieboldii and Lithocarpus edulis, are not bitter, they can be roasted and eaten as is, but because most acorns, including those of the jolcham oak, Mongolian oak, and sawtooth oak, contain large amounts of tannin, animals cannot eat many at one time no matter how nutritional the nuts may be.

For example, an experiment conducted on large Japanese field mice revealed that those eating only acorns developed digestive problems and died. If, however, the field mice mix acorns with their usual food and eat a little bit at a time, they can survive. This is called “acclimation.“ Oak trees producing a large amount of nuts all at once is a tactical maneuver on the part of acorns to leave behind just the amount necessary for producing the next generation, even though a portion of them will be eaten. By contrast, if there are no acorns, squirrels, field mice, and Eurasian Jays may not have enough to eat in winter. They cannot survive only on acorns, but they are an important food resource in winter. There is a strong “co-evolutionary” relationship that exists between acorns and food caching animals.

Spotted Nutcracker living high up in the mountains, around 3000 meters, makes its loud call of “ga-, ga-.” It is probably a familiar bird to mountain climbers. The feathering over its body is predominantly a chocolate brown with distinct white spots and streaks like stars. It resides in coniferous forests from Hokkaido to Honshu and the subalpine to alpine belts of Shikoku. The Spotted Nutcracker loves the fruit of the Japanese stone pine and the Japanese white pine. Hiking in the mountains in autumn, I came across a Spotted Nutcracker with a gular pouch full of seeds, carrying them to its cache sites. Watching it closely, I also saw some of the places where it was hiding food, including a cliff crevice and under a rock beside the hiking trail.

The Japanese white pine would not grow if it were not for the Spotted Nutcracker. That is because, for some reason, the nut of the Japanese white pine cannot germinate on its own. For a shoot to come up, a collaborative effort in which a number of nuts that have been buried in the ground germinate at the same time and push through the soil to the top is required. So, if it were not for the Spotted Nutcracker, the Japanese white pine would not be able to propagate. The two have built a mutually beneficial symbiotic relationship, the Spotted Nutcracker depending on the Japanese white pine, and the Japanese white pine depending on the Spotted Nutcracker.

Wildlife ecologist

Professor Emeritus, College of Science at Department of Life Science in Rikkyo University

Former President of the Ornithological Society of Japan

Born in 1950 in Osaka Prefecture. Areas of research include evolutionary ecology of plants and animals with particular focus on avian species, and also environmental issues. Vice-president and Trustee member of the Wild Bird Society of Japan. Currently works as editor in chief of Strix, a member-authored journal of field ornithology, published by the Wild Bird Society of Japan.