Let's go bird watching! Vol.3

Bird watching in autumn

For birds, autumn is the season of migration.

Summer birds, such as swallows and members of the Muscicapidae and Cuculidae families, migrate from Japan to Southeast Asia for the winter. Conversely, many species of geese, duck, swan, and gull migrate to Japan after raising their young on the tundra of Russia and other such places.

Envision the tundra in winter. You can surely imagine the problem that waterfowl face as lakes freeze over in the bitter coldness of subzero temperatures, making it impossible for them to find food. In the face of such severe winter conditions, migration to a warmer place where there is more food to eat is essential for survival in the wild.

However, migration is a very grueling experience. Some birds give out en route while others fall victim to raptors, such as eagles and hawks. Many young birds born in the spring each year cannot make it through their first winter. When you think of the dangers involved in migration, you could say that winter is a harsh season no matter what, whether birds stay where they are or migrate somewhere else.

Incidentally, the regular seasonal movement between breeding and wintering grounds is called “migration.” Finding out which birds go from where to where is a difficult task. While the migration of some birds, such as the Brown-eared Bulbul, can be seen throughout the country, the movements of other species that are seen year round, such as the Japanese Tit, are not well known. And there are some birds, such as sparrows, whose young birds “disperse” long distances in autumn, which is different from migration.

Bird watcher's report:

Text and photos by a member of the Canon Bird Branch Project

Members of the Canon Bird Branch Project gathered at Tokyo Port Wild Bird Park in the morning of a clear autumn day in the middle of October. Continuing on from the excursion in May, our instructor that day was Mr. Hideaki Anzai, Consultant at the Wild Bird Society of Japan.

While looking at a map of the park along the road close to where we got off the bus, he enthusiastically told us about the park: how it looked when it was first established, the kinds of trees planted there, and other such details. Having a connection to the construction of the park some 30 years ago, it seems to have a special place in his heart.

1

Just as we arrived at the main entrance to the park a few minutes' walk from the bus stop, Mr. Anzai cut short the conversation as small birds flying above caught his attention.

The theme for the day was autumn migration and waterfowl, and as if on cue, the first birds to cross our path were a flock of migrating Brown-eared Bulbuls flying the wrong way.

How did Mr. Anzai know that the birds were heading in the wrong direction?

Many birds migrate in flocks to more temperate areas south or west in autumn, including Brown-eared Bulbuls. This flock of bulbuls, however, was heading in a northerly direction.

According to Mr. Anzai, birds on a long-distance migration seem to rely on the stars to hold their course at night. On the other hand, migrating birds that fly during daylight, such as Brown-eared Bulbuls, are thought to get their bearings from the position of the sun and their internal clock. The weather that morning was unstable, and because the sun came out after their departure time (this time it was about 10 am) they lost their bearings and seemed confused.

So, birds are able to correctly navigate to their destination thanks to their ability to read the stars and the sun. That makes sense. But in conditions such as those today, their internal navigation system can get thrown off it seems.

2

Mr. Anzai posed a question: “Even though many species migrate, why do we humans not really notice it?” Come to think of it, that is true, I do not take much notice.

That is because long-distance migrations are often done at night. It would be difficult to continue flying with the sun beating down on its back (energy expenditure is intense), but the advantages of flying at night are the coolness of the dark hours and safety from raptors such as hawks and falcons. And, daytime migration when energy expenditure is high requires more stops for feeding than nighttime flying. Repeated short breaks bring greater danger. During the night, birds can fly long distances uninterrupted and without looking out for natural predators, making it much safer for them.

There are also birds that migrate during daytime. These include birds such as swallows that can forage for food during flight, raptors such as hawks and falcons that have few natural predators, and large birds such as swans and cranes that make use of air currents. It seems that birds such as Brown-eared Bulbuls that start their migration in the morning take off early and finish their flight before the sun rises high.

3

Before going to see the waterfowl, the main target of our excursion, we headed to the ecological gardens, which are part of the original park grounds. We arrived at Observation Hut 3, and after we sat down to look over the pond through the observation window, Mr. Anzai let us know that a Common Kingfisher was there. We all became excited.

The Common Kingfisher is popular for its beautiful colors even among non bird watchers. Here at the Wild Bird Park you can observe them year round.

Mr. Anzai threw out a question: “Kingfishers are no doubt smaller than you think, but how small do you think they are?”

Someone replied, “Maybe the size of a sparrow?”

“That's right. They're very small, but they have a shrill call that sounds like “Chii,” and since their coloring makes them stand out, they're easy to spot.”

Certainly, despite their small size they do tend to stand out, so we were all able to find it quickly.

And, it looked like there were actually two birds, not one. Most probably, they were hungry, they just perched on the branch and suddenly dove in the water to try and get fishes. It seems it was focused on hunting and not about to fly away. Watching it boldly dive again and again with its small little body was not simply cute, it was cool! Holding a fish firmly in its bill, it would also strike it on the branch. Sometimes it would hide in the shadow of a branch and change its position, but we were really lucky to be able to watch it for quite a long period of time. I was very happy with the bird watching that day right from the start of our excursion.

Having had a good look at the kingfisher, we headed over to the East Freshwater Pond for the ducks, our main target of the day.

Along the way, a Japanese Pygmy Woodpecker, the smallest of the Picidae family, suddenly appeared. They are also small like a sparrow and very cute. Though it was only two or three meters away from us, it showed no signs of flying away.

Mr. Anzai explained that Japanese Pygmy Woodpeckers are not very cautious, and even if humans come up quite close they do not fly away. You can almost reach out and catch it in your hand.

I was not expecting to see any woodpeckers at all, but according to Mr. Anzai, they also live in city parks nearby and are not that uncommon. And, since they are “resident birds,” they can be seen year round.

When Mr. Anzai was young, these woodpeckers only lived in the forest, so it was not a bird that was frequently observed. Why is it that they can now also be seen in cities?

Knocking on a dried-out, hollow-sounding tree without a single leaf on it, Mr. Anzai explained: “It's likely that's because there are more decaying trees now as a result of aging and disease among some of the trees in the park that have matured over the past several decades. These trees are a dining room for woodpeckers. If you want to observe a woodpecker, find a dead-looking tree. There are lots of insects in a rotted out tree like this. Decaying trees attract the insects.”

Right after saying that, a Japanese Pygmy Woodpecker came to the tree.

So, your chance of seeing a particular bird increases if you find the tree or environment that it likes and wait there patiently.

There were actually two Japanese Pygmy Woodpeckers that came along, not just one, and I was able to carefully observe them at a close distance for the first time.

We walked along a little farther, and suddenly Mr. Anzai asked, “Do you smell soya sauce?” as he began picking up a few fallen leaves. Beside us was a katsura tree. Come to think of it, I have heard that name before. With a preference for rich moist soil, the wood of the katsura tree is soft and easy to process so it is used in billboards and the like.

Sadly not so many birds come to it, but as autumn progresses the leaves change from green to yellow. If you smell soya sauce when you are out for a walk, look for a katsura tree.

4

The Tokyo Port Wild Bird Park was born out of the desire of local residents to make the most of the restored nature on reclaimed land. A rich variety of ponds, including freshwater ponds and a brackish water pond, are compactly arranged on the grounds, and a variety of birds can be observed in their preferred environment.

Located a relatively close distance from the city center, and offering the opportunity to observe various species of duck and heron as well as cormorants in autumn and winter. And various species of sandpipers and plovers can be observed in spring and autumn. The park is a popular spot for bird watchers year round.

Today too there were herons and cormorants, which are always around in Tokyo Port, as well as many ducks, our target for the day, gathered in one area of the pond.

Cormorants are easy to distinguish, as are herons, but how many kinds of species of duck are in this pond?

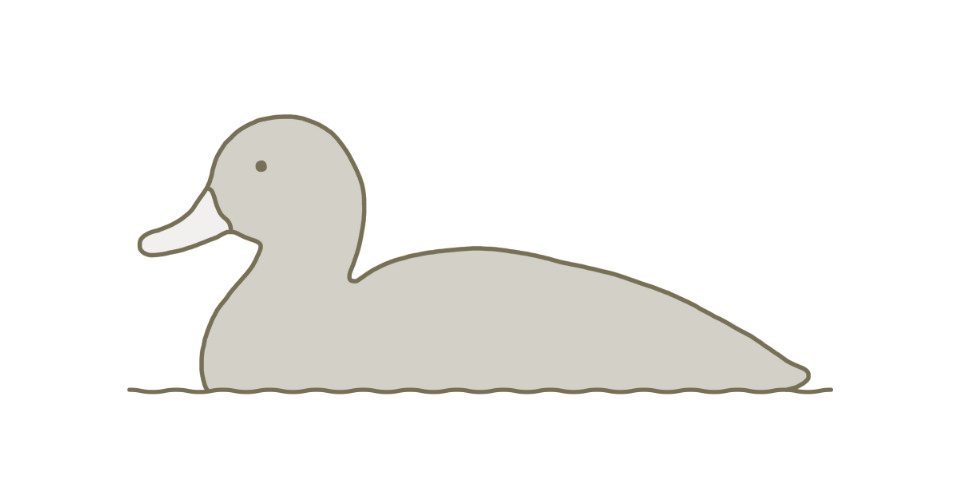

The only species that can be seen here at Tokyo Port Wild Bird Park year round is the “resident bird” Eastern Spot-billed Duck.

Between October and March, there are many ducks at the park. During this period, there are about a dozen species of duck alone, and together with other species of waterfowl about 30-40 species can be observed.

Mr. Anzai notes, “There are birds among them that we think are ducks but actually not. For example, that black bird there is not a duck.”

By their appearance, we know that herons, cormorants, sandpipers, and plovers are not ducks. But that black bird is casually swimming on the surface and sometimes diving down in the water. Is it not a duck?

Mr. Anzai explained: “That is a coot, which is classified as part of the Rallidae family in the Gruiformes order, with its distinctive white forehead. Ducks have a flat-looking bill from the side, but the bill of the coot is pointed.”

So, you should not think that all the birds swimming on the surface are ducks. I learned something new.

When the tide goes out, sandpipers and plovers skitter over the mud flats, picking up crabs, mussels and other shellfish. The fact that we can leisurely watch them since they are preoccupied feeding is a big draw.

5

Our target today was ducks and other waterfowl. So, that being the case, we headed to the Brackish Water Pond at the Nature Center. There were lots of ducks spread about the wide pond.

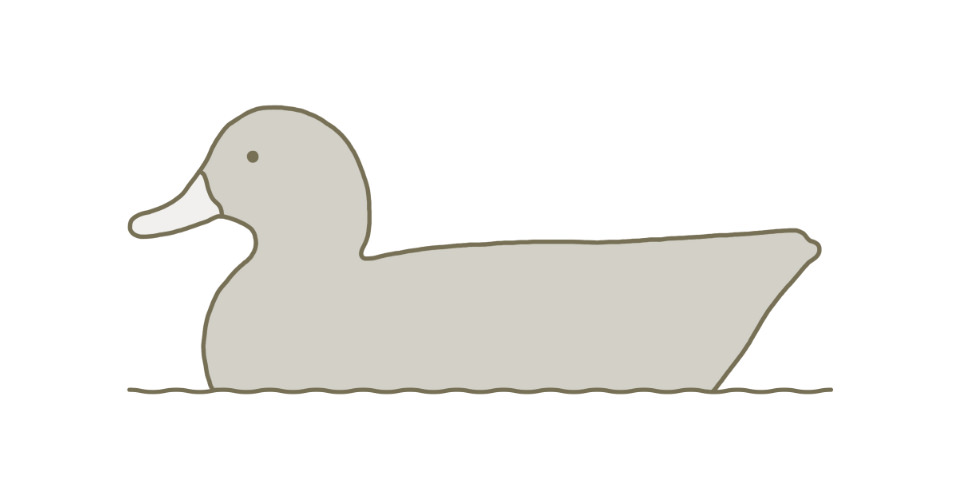

Now Mr. Anzai gave us an instruction: “Look at the rumps of the ducks!”

He continued with an explanation to the bewildered members: “During this season when males are not showing colorful plumage and it's difficult to distinguish species, let's try and distinguish which ducks are divers and which are not.”

I thought all ducks are divers….

“Ducks whose rump slants downward and have a low center of gravity are divers. Ducks whose rump slants upward are not divers.”

So, there are certain bodies and shapes designed favorable for diving and unfavorable for diving. For sure, ducks that dive have tails that look like they go downward.

Mr. Anzai continued: “Ducks that dive underwater feed on algae and bottom fauna. Ducks that don't dive feed by skimming the water surface with their bill for grass and other aquatic plants.”

Diving ducks also have legs set well back on their torso, which necessitates they taxi across the water for takeoff. Since it is easier to escape from predators when in the water than on land, they spend more of their life on the water, apparently even resting and sleeping there too.

On the other hand, non-diving ducks do not need to taxi for takeoff, and they go to shallow areas to preen, rest and sleep.

I now understand that body structure and food source, habitat, and lifestyle are connected.

For beginner bird watchers like us, identifying variations is quite difficult, so it was really helpful to learn from the rangers for the park.

6

At the East Observation Blind, there are many land birds, including Large-billed Crow, Oriental Turtle Dove, Bull-headed Shrike, and White Wagtail, in the dry land area. Since the Bull-headed Shrike was calling “Kii-kii” with a high-pitched, strong voice, we could thankfully locate it easily.

The Bull-headed Shrike is often said to have a high-pitched voice, but why does it shriek in the autumn or winter when it is not the breeding season?

Mr. Anzai acknowledged that is a good question.

He responds saying, “Because the majority of small birds have the advantages of being able to easily find food and detect predators, in winter when food is scarce they gather together in flocks. But, Bull-headed Shrikes are carnivorous hunters who get through the harsh winter on their own. So, in order to protect a territory having food resources, they stake a claim. Although many other species will stay in the same tree, they are not rivals since their life habits and feeding habits are different. The claim is strictly against those of the same species (shrikes).”

All of a sudden, the Large-billed Crows start making a ruckus, dispersing to the surrounding trees.

“That's what they do when a raptor is around,” Mr. Anzai explained.

Up in the sky is a Black Kite.

“Mr. Anzai, are they alarmed by the Black Kite?”

“No, no,” he replied with a slight laugh, “crows aren't concerned with kites.”

Looking higher, there was another raptor in the sky above the kite.

Mr. Anzai declares, “It's a Common Buzzard. That's what the crows were on the alert for.”

Aquatic areas where many ducks gather also bring raptors, such as the Northern Goshawk and the Common Buzzard, who target waterfowl that are slow to escape or that are sick or injured.

If you notice not only crows but also ducks on alert, it may be a chance for you to observe a top predator in action!

Today, since we were out for autumn bird watching, primarily focused on ducks, we were even able to observe some species of hawk that target ducks as prey. Ducks migrate to Japan where there is food for them, and the raptor species that hunt those ducks hang around ponds where they gather. That is the food chain in action. For the Japanese Pygmy Woodpecker too, because there are rotted out trees that provide food for them, they have come out from deep in the forest to city parks. I fully understand how this kind of food-rich natural environment creates an environment overflowing with life.

On the next dry, sunny day, why not take a walk in a nearby park with a patch of water and see what you can find!

Oriental Turtle Dove, White-cheeked Starling, Brown-eared Bulbul, White Wagtail, Eurasian Tree Sparrow, Azure-winged Magpie, Large-billed Crow, Bull-headed Shrike, Black Kite, Common Buzzard, Eastern Spot-billed Duck, Mallard, Teal, Northern Pintail, Gadwall, Common Pochard, Tufted Duck, Eurasian Wigeon, Falcated Duck, Little Grebe, Great Egret, Little Egret, Grey Heron, Great Cormorant, Coot, Common Kingfisher, Japanese Pygmy Woodpecker

Birds confirmed only by their voice: Japanese White-eye, Japanese Tit, Oriental Greenfinch