Let's go bird watching! Vol.5

Bird watching at the beginning of autumn

In a four-season country like Japan, the short period of changeover when you can experience two seasons at once is a special time. In the latter part of August, in addition to the songs of summer insects such as the large brown cicada, you likely notice songs that signal the end of summer, such as that of the Walker's cicada. At night, you can hear the chirping sound of crickets. It is thought that the reason why crickets are thought to be autumn insects is because during the hot season they chirp on cool evenings, but in autumn they can also be heard during the day.

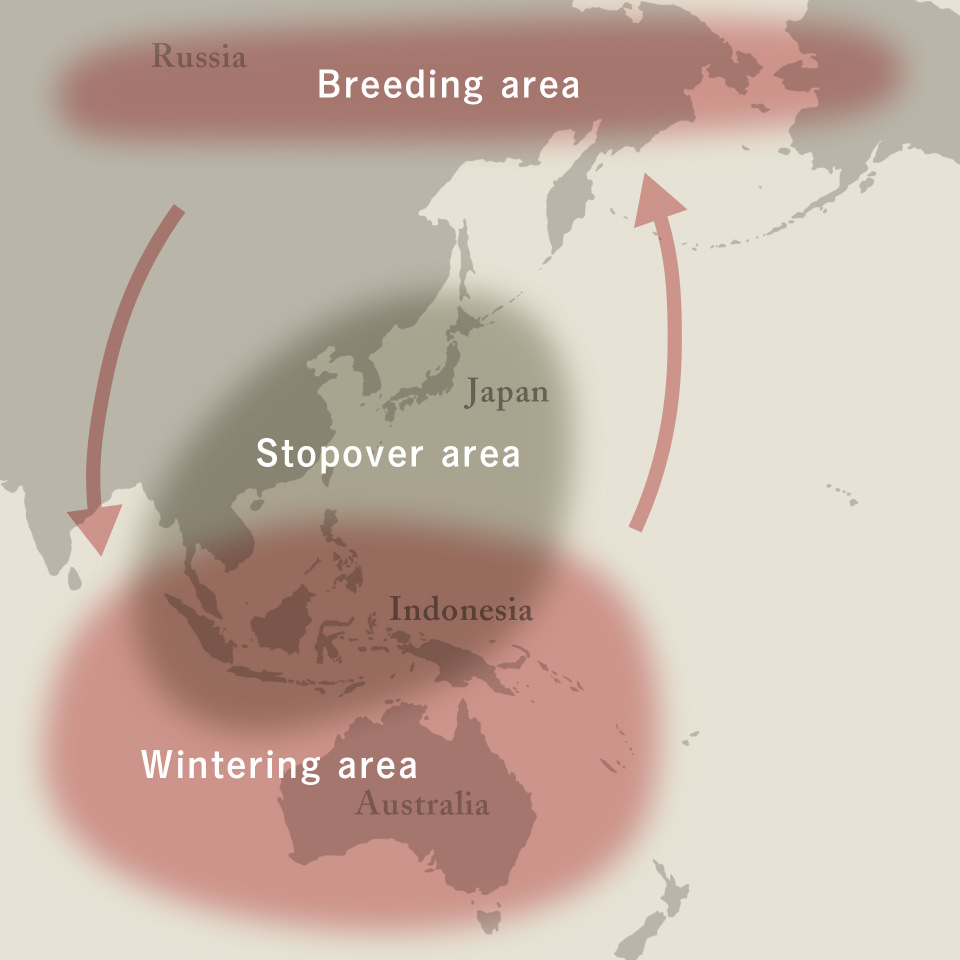

Now, you could also say that, in the bird world, summer is not a very good season for observation. The reasons for this being that in summer birds stop actively singing when the mating season ends and many become less active when they are molting. Sandpipers, however, are an exception. Many species breed in the Arctic and then make the long journey to winter in the Southern Hemisphere, so in August the birds have already left their breeding ground for the south, with several species making a stop in Japan. Spring and autumn are the seasons for migration, but for sandpipers, autumn migration starts in August. Many species of sandpiper heading south stopover in Japan between August and October, so by all means, take the opportunity to observe them at the waterside, especially on tidal flats where they are often found.

In recent years, the global decline in sandpiper and plover populations has been notable. The population of migratory waterbirds has declined between 5% and 9% yearly, and one of the reasons for this is believed to be the reclamation of tidal flatlands in both stopover and winter destinations.

To protect bird species that migrate over long distances, some more than 10 thousand kilometers, initiatives to protect essential habitats must be promoted internationally. The East Asia-Australasian Flyway Partnership is an international initiative to protect migratory waterbirds. Partners, of which Japan is one, include national governments, inter-governmental agencies, and international non-government organizations.

Bird watcher's report:

Text and photos by a member of the Canon Bird Branch Project

This time our outing was in late August, when the summer heat is still stifling. Wanting to feel the approach of the coming autumn season, we visited Yatsu-higata (higata means tidal flat in Japanese) in Narashino-city, nearby Tokyo, to observe sandpipers.

Amid the reclamation of tidal flats in Tokyo Bay that began in the 1950s, Yatsu-higata was preserved in response to pressure from citizens and environmental organizations for its protection. Covering 40 hectares, the tidal flat is relatively small, but in 1988 it was designated a National Wildlife Protection Area, and in 1993 it was internationally recognized as an Important Bird Area (IBA) and registered as a Ramsar Convention Wetland.

Access from Tokyo is very convenient, thirty minutes by train from Tokyo Station and then a few minutes' walk from JR Minami-Funabashi Station to reach the tidal flat itself. Walking along the trail on the periphery of the tidal flat for about fifteen minutes brings you to the Yatsu-higata Nature Observation Center.

This time we met at Minami-Funabashi Station at 10 am, and leisurely made our way along the trail observing the tidal flat so we would arrive at the restaurant in the observation center for lunch.

1

What is the most important thing for observing birds on a tidal flat?

It is choosing the day and time of your outing.

Birds come to tidal flats for the purpose of feeding.

In particular, since the small creatures that sandpipers and plovers feed on appear when the tide is low, it is good to remember that the birds are often resting somewhere else when the tide is high. In order to see sandpipers and plovers, you must check the timing of the tides in advance.

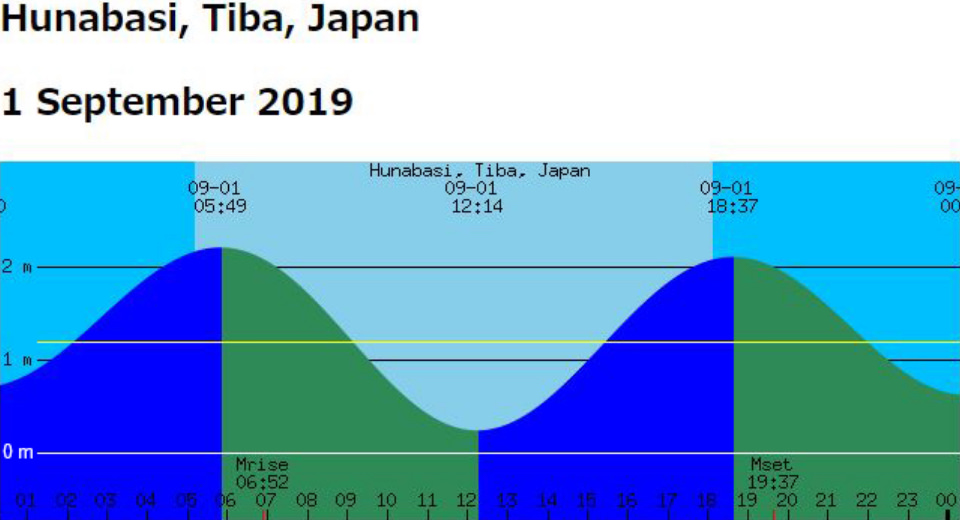

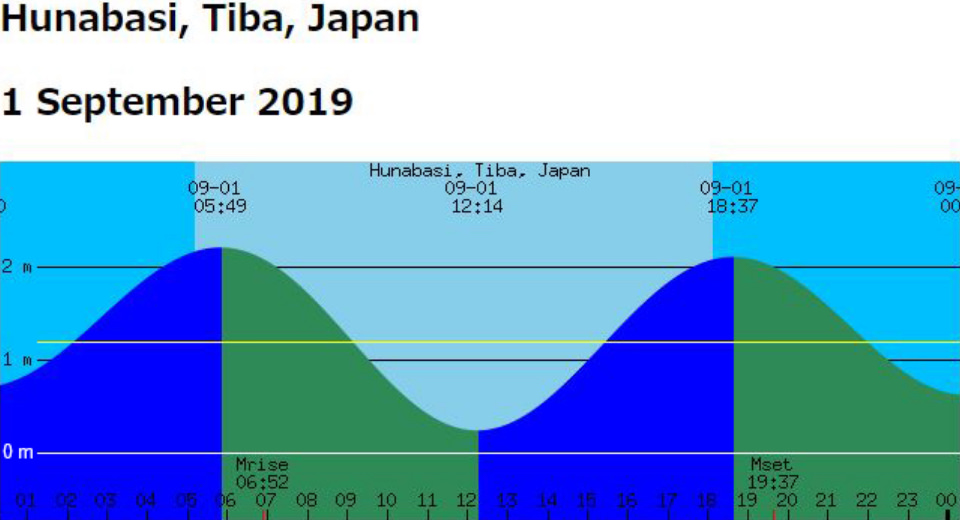

So, how do you check the timing of the tides? I recommend using the WWW Tide and Current Predictor website. When you select the month and day you want to go bird watching, you can see a graph of the tides for that day, which is very convenient.

For example, in the sample graph of tides, the time when the vertical line is close to 0 m is the low tide. According to Mr. Anzai, the best time frame is the hour before and after low tide. This is the time when the water level slowly decreases and you can see the complete change to a tidal flat. For our visit to Yatsu-higata, we decided our meeting time based on information we discovered indicating that low tide for the tidal flat is 90 minutes later than what is indicated on the tide prediction graph for the Funabashi area due to its inland structure, which resembles a swimming pool, enclosed by concrete on all sides and connected to Tokyo Bay via two channels (on the western and eastern ends) that are accessible by tidal flow.

2

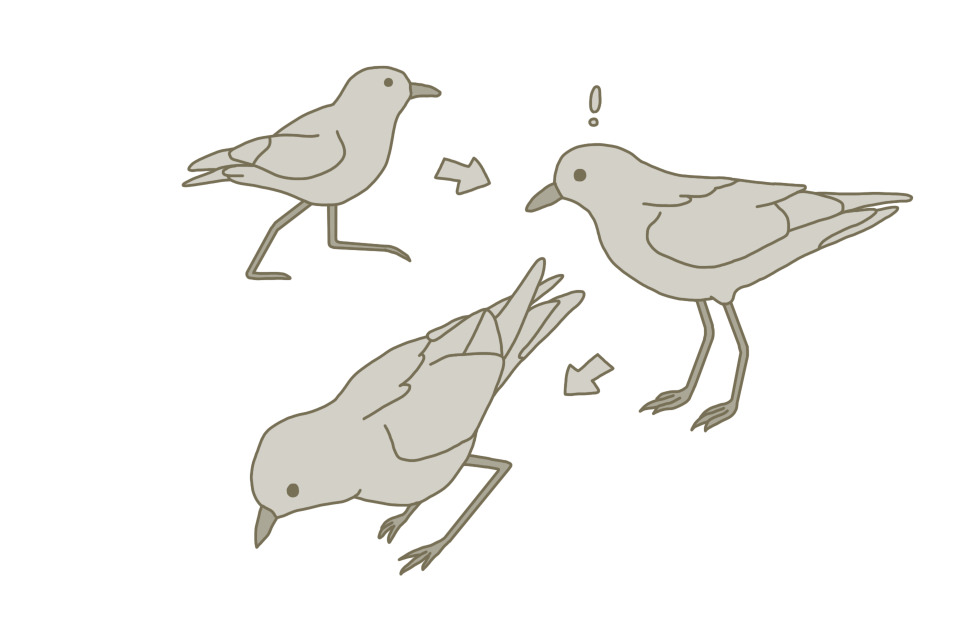

We arrived at the tidal flat. The tide had not fully gone out yet and there were some Eastern Spot-billed Ducks,, often seen near water, milling about. Although it is a bird we often see, Mr. Anzai stopped and said, “Look carefully at its feathers!”

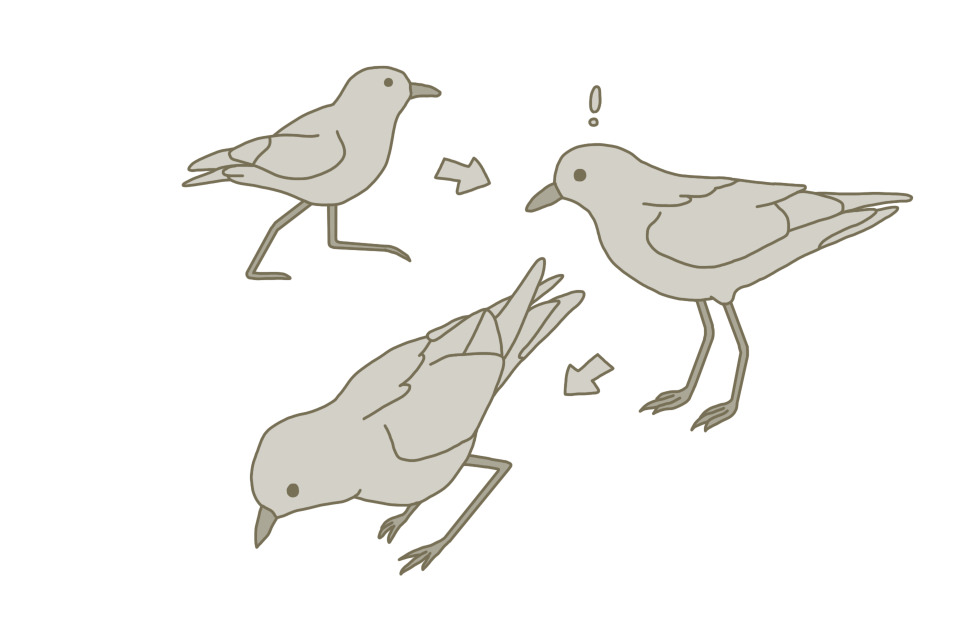

He continued, “Around this time, ducks lose their feathers about 20 feathers on each wing, all at one time, so now they can't fly.”

Then came the question:

“Since they're birds, it can't be that they can't fly at all, right?”

Mr. Anzai replied, “When they lose their flight feathers they can't fly at all, they can only walk and swim.”

The period when birds change their feathers, called molting, begins after the breeding season ends, and since feathers, such as the flight feathers, are shed a few at a time in an orderly way, they usually do not become completely unable to fly. Ducks, however, are an exception; since they lose their flight feathers all at once, they are unable to fly until new flight feathers grow in.

A worried member asked, “What if a hawk comes after it? It can't get away, can it?”

Mr. Anzai replied, “Ducks that can't fly during molting usually spend the time near bushes or reed beds where they can hide. But….”

It seems that molting Eastern Spot-billed Ducks had been spotted in grassy areas such as reed beds of lakes and rivers, but in recent years they have frequently been seen at park ponds in residential areas. Since enemies such as raptors and animal predators are fewer in urban areas, they are now spending the molting season in places close to human activity.

When they fold in their feathers it is difficult to see the layers, but looking closely we saw that there were some Eastern Spot-billed Ducks that definitely had flight feathers growing in.

3

As we carried on with our walk, it seemed that the water level was slowly falling. As we saw the change to a tidal flat, we could see many little snail shells on top of the mud. Crabs also appeared here and there, busily exercising their claws and carrying things to their mouth.

Mr. Anzai explained a little about crabs: “Look at the eyes of the crab. Do you notice that they are in a high position so they can look in every direction? They can even notice when birds such as sandpipers try to attack them from behind.”

According to Mr. Anzai, a tidal flat is an important environment for cultivating biodiversity. It is also an environment of high biological productivity, and it plays a role in purifying seawater.

Several small benthic organisms, like sandworms, shellfish and crabs, live on tidal flats, and many of them play an important role in filtering organic matter, taking in sand and mud and then expelling it after absorbing the organic matter.

The rise and fall of the tides depends on the action of the sun and moon, and the oxygen that adheres to the surface of the tidal flat after the tide goes out is supplied to the seawater when the tide comes in. The small organisms of the tidal flat dig holes in the mud, and birds run around chasing after the small organisms and peck in the mud, thus expanding the surface of the tidal flat and generating a greater supply of oxygen. The oxygen activates the bacteria in the water and also promotes the decomposition of organic matter.

For many members, their image of tidal flats was of clam digging, and they learned for the first time the vital importance of tidal flats to the global environment.

4

When the tide goes out and the tidal flat is exposed in parts, sandpipers and plovers come in search of small creatures. We heard a melodic call of “pyuee, pyuee.” It was the voice of a Grey-tailed Tattler, and when Mr. Anzai hears this call he feels the coming of autumn even in the heat of summer.

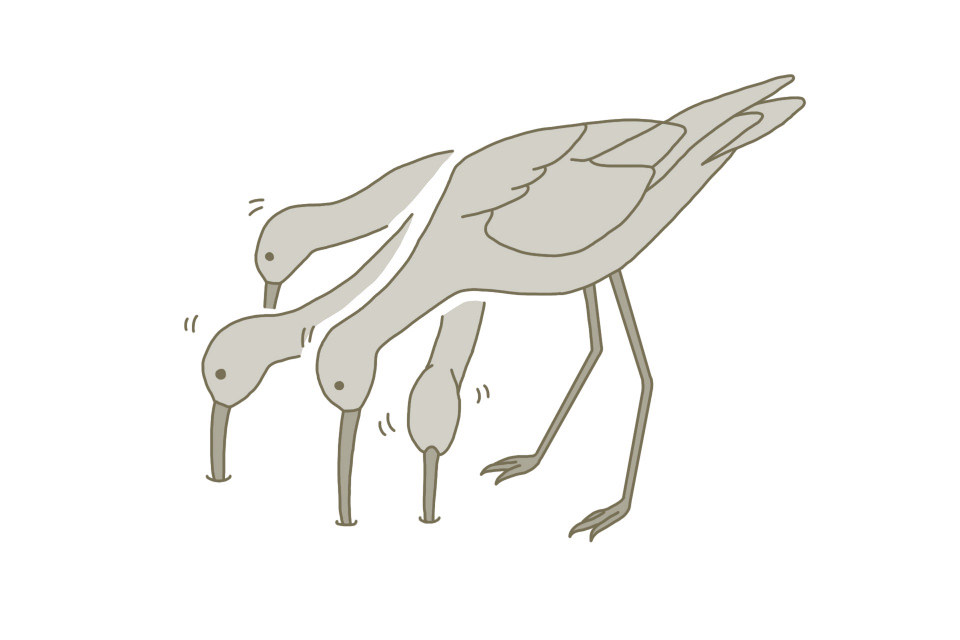

Sandpipers and plovers feed on crabs, sandworms and various types of clam. They run about busily pecking the ground.

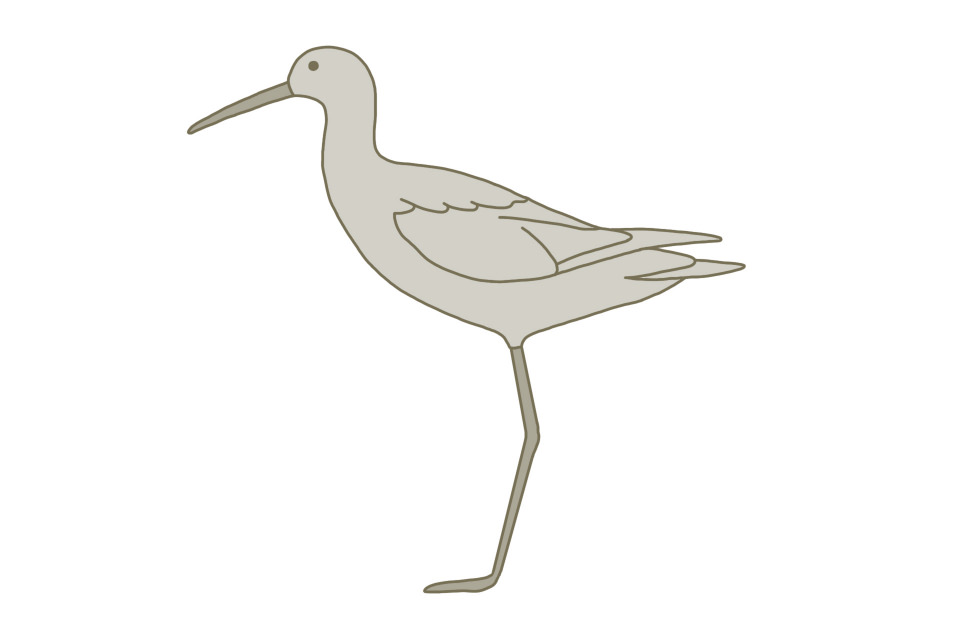

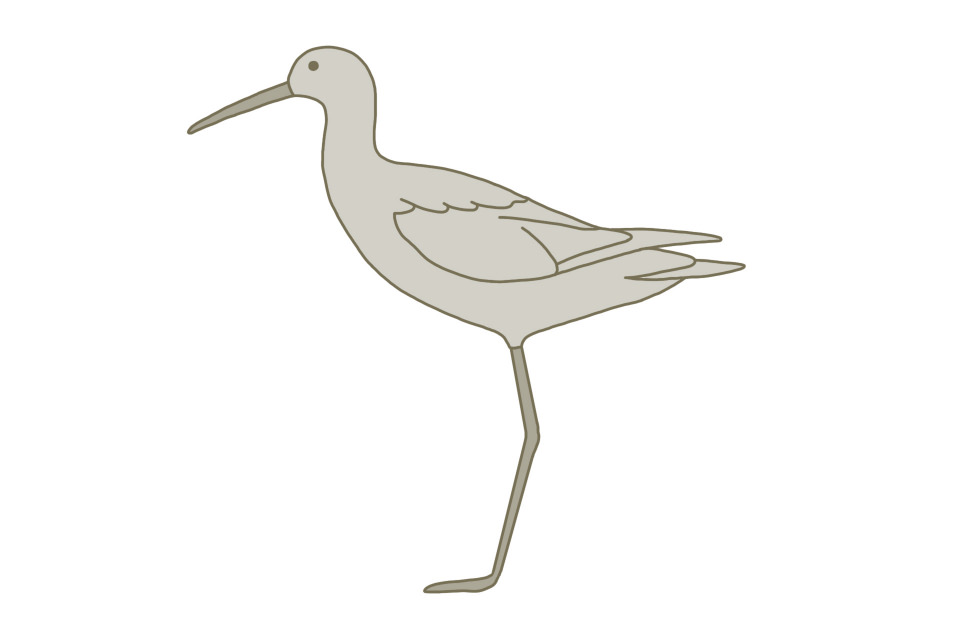

Here, Mr. Anzai taught us how to distinguish between sandpipers and plovers. Since both run around at the water's edge, they both have legs that are longer than other small birds, but birds with a long bill are members of the sandpiper family and those with a short one are related to plovers. Sandpipers can stick their long bill into the mud. The tip of its bill is sensitive, and not only does it have outstanding tactile perception, but it can also open and close its bill while probing in the mud to pick up small prey. Short-billed plovers, on the other hand, rely on their keen eyesight to find and snatch up prey on the ground.

My first-glance impression is that sandpipers are the “models” with their long bill and long legs, and plovers are the cute “pop stars” with their small body and big round eyes.

Today, the only two plovers we saw were a Grey Plover and a Mongolian Plover and sadly we did not encounter a large flock of sandpipers, but according to Mr. Anzai, there are occasions when flocks numbering into the double and even triple digits can be observed. But, since we are dealing with animals in nature, whether you see them or not is all about luck. We heard from other visitors who had come for bird watching that they encountered many sandpipers at another tidal wetland close to Yatsu-higata earlier that day.

5

The water level rose gradually as we observed the sandpipers and plovers for some time. The tidal flat grew smaller and puddles of water increased. Still, there were some sandpipers and plovers lingering here and there.

One of the members commented, “That Grey-tailed Tattler is still on the hunt to the very last!”

There were definitely a few Grey-tailed Tattlers that were not giving up the search for prey, moving quickly to the remaining open areas of the tidal flat as if being chased by the incoming tide of seawater.

Mr. Anzai explained, saying, “They feed for as long as they possibly can! Seeing this you can understand what a great source of food the tidal flat is, and how birds that migrate long distances have to refuel and replenish their energy when and where they can.”

The sandpipers and plovers that are here at Yatsu-higata now, and those that will travel south along the Japanese archipelago from here are birds that have finished breeding and rearing chicks in the northern regions that serve as breeding ground, such as Siberia and Alaska. Many adult birds of sandpipers and plovers reach in Japan by August. And since the number of juvenile birds increases from September onward, it seems that the young birds are a little slower in making the journey. They are heading for winter destinations such as Southeast Asia, Australia or New Zealand, and it could be said that Japan is a stopover spot along the way.

“How far do they fly at one time?” asked a member.

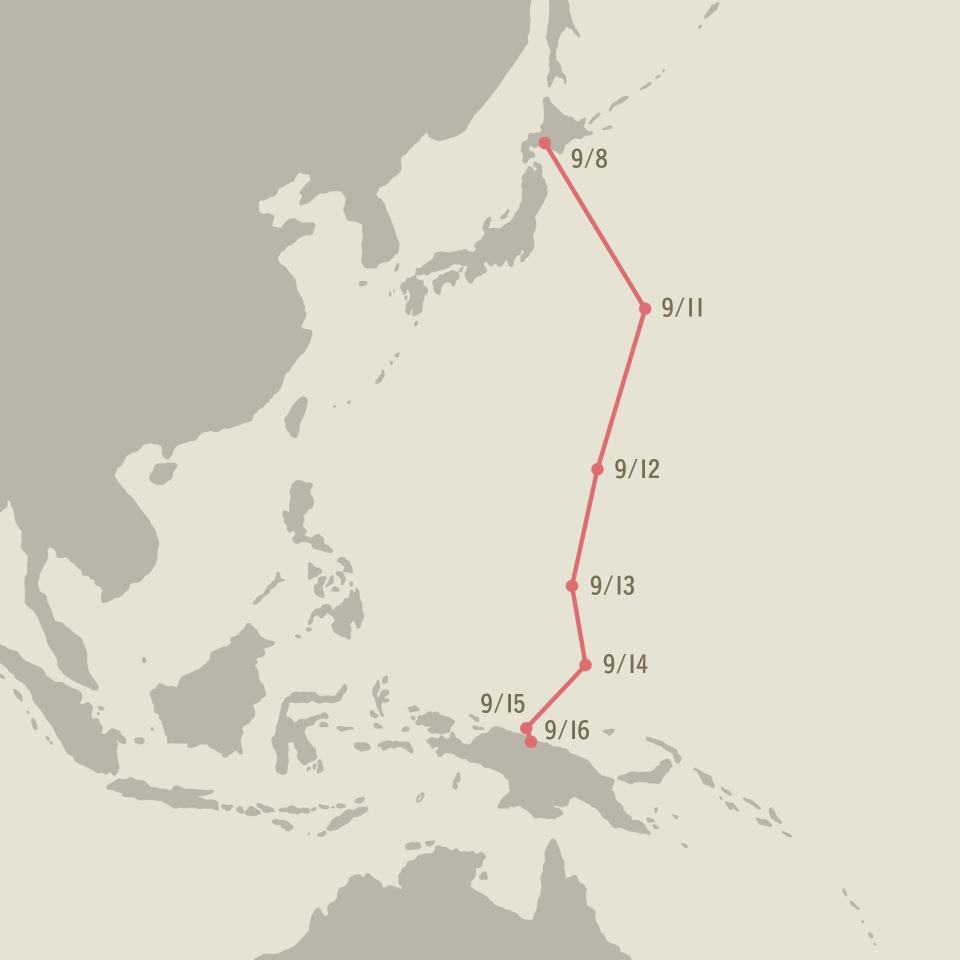

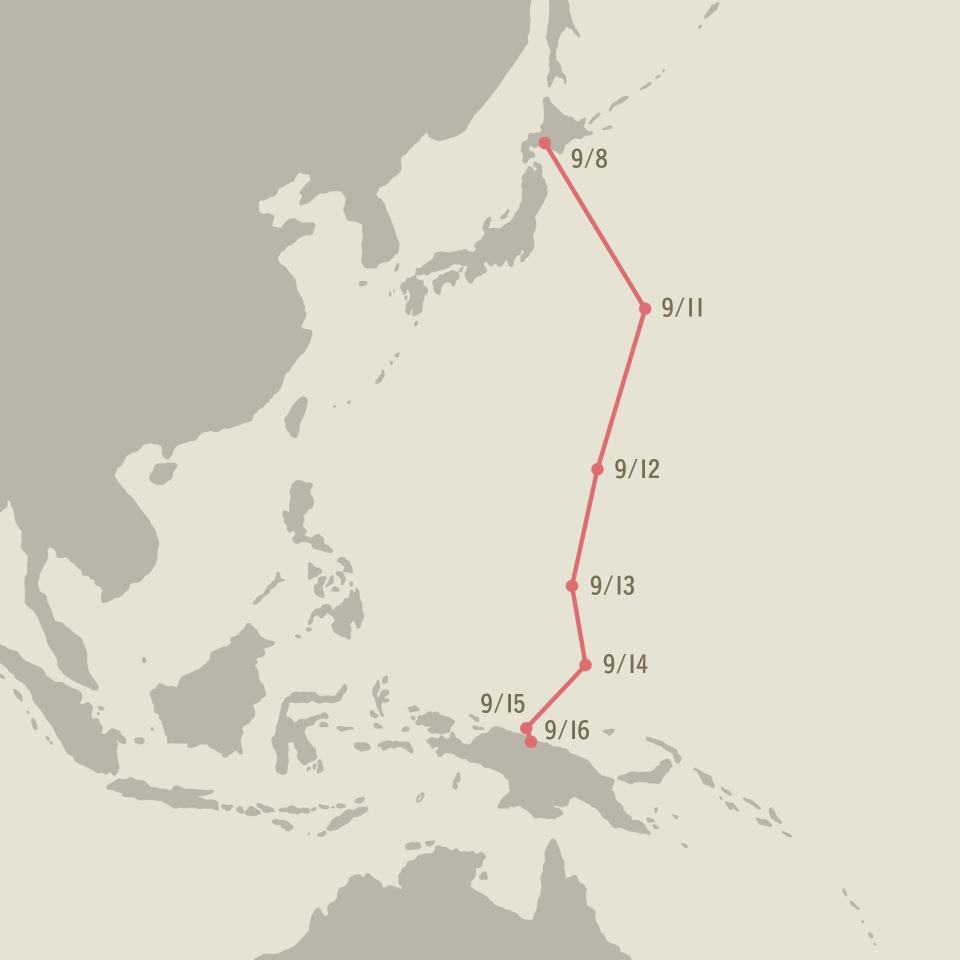

Mr. Anzai replied, “It was thought that they made the long journey by easy stages, repeatedly feeding and resting up at tidal flats along the way, but in recent years we've come to know of cases when birds have made the long journey all in one go.”

“For example, research by the Wild Bird Society of Japan, which involved attaching satellite-tracking devices to Latham's Snipes, revealed that some birds flew for a week non-stop, and that they were able to cover distances close to 900 kilometers in one day.”

Whatever the case may be, they are probably hungry when they arrive in Japan, and have to eat as much as they can before carrying on in their journey. To all the sandpipers and plovers I say, “Eat as much as you can now!”

One of the rangers told us two birds that have been observed here at Yatsu-higata for nine consecutive years were confirmed through this tracking program. In the natural world there is always the possibility of bad weather, predators, sickness and injury. We were so impressed by that amazing record of birds surviving the journey back and forth over nine years.

6

“Oh, it looks as if the Great Cormorants have started drive fishing,” quipped Mr. Anzai.

Some Great Cormorants, some of whom were leisurely perched atop posts spread here and there across the water while others were engaged in the quintessential activity of drying their wings, had formed a flock and were swimming energetically.

A member posed some questions: “Is there a leader within a flock of Great Cormorants? When and how do they gather together?” To be sure, they were moving about in an organized way. Is the one at the front the leader?

“No. Many bird flocks are not social in nature, so it is not the case that one bird becomes the leader and gives direction to the others. You often see starlings and sparrows in flocks, but it seems that their reason for flocking together has to do with safety in numbers, that is protection from predators. For Great Cormorants, they each want to feed so in the end they gather together since it appears that the fishing is better if many birds surround a school of fish and drive it, rather than just one bird fishing alone, and that's why it can be called ‘drive fishing’.”

There are also many white herons. Large herons are Great Egrets, and small herons are Little Egrets. The naming is very simple to understand. The mid-sized heron known as the Intermediate Egret, however, is not often seen on tidal flats.

“Mr. Anzai, there aren't any Intermediate Egrets here, are there?”

He responded, saying, “Intermediate Egret is registered as Near Threatened on the Ministry of the Environment's Red List in Japan. Since they prefer freshwater wetland areas, you more often see them in rice fields.”

“So, for the white herons here on the tidal flat, am I right in thinking that the large ones are Great Egrets and the small ones are Little Egrets?”

“Usually that's correct. But, size can vary depending on the distance and the angle of view, so it's good to have something to compare it to. For the Great Egret, a good size comparison would be the Grey Heron. And, from late August, when the breeding season ends, into autumn birds are on the move and migration is starting, so you may see birds that are not usually around.”

According to Mr. Anzai, the Intermediate Egret is a summer bird in areas north of the capital region (Tokyo) that heads south in autumn and winter and is no longer seen until spring, but a stopover in the tidal flat is also possible at this time of year.

Just then Mr. Anzai cries out,

“Oh! I wonder if that's an Intermediate Egret?!”

It was an Intermediate Egret.

All of the members were able to observe for the first time an Intermediate Egret, which I had thought was rarely seen.

We observed many other birds near the water in addition to these, including the Black-necked Grebe, which constantly dives to catch prey, along with some summer gulls, such as the Black-tailed Gull, and the Little Grebe in the freshwater pond.

7

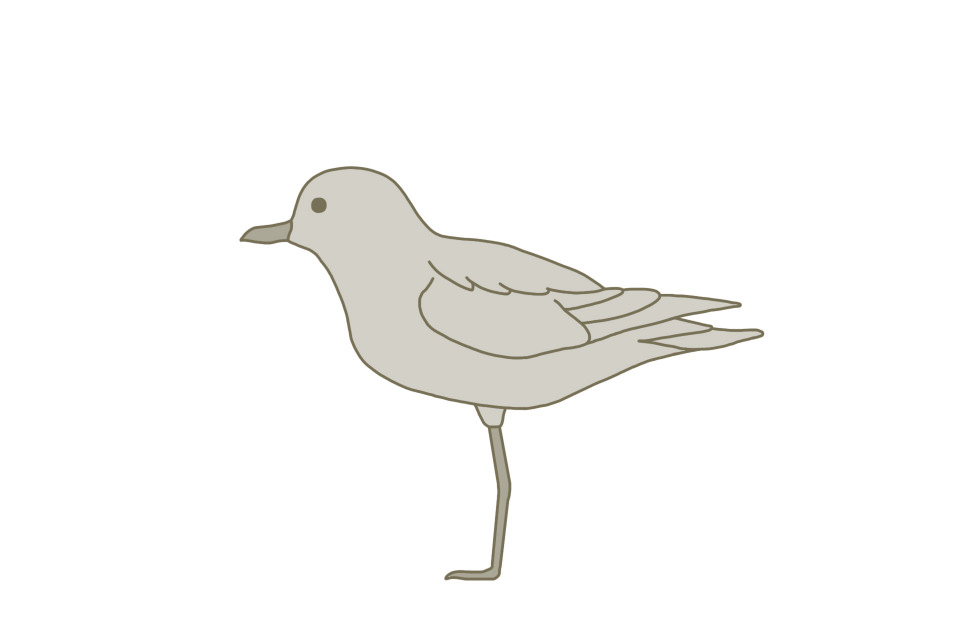

Mr. Anzai encouraged us to look around carefully since juvenile birds are distinguishable up to the beginning part of autumn.

Birds grow quickly: usually chicks born in spring leave the nest within 2 or 3 weeks and enter the stage when they are known as juvenile birds, reaching independence by the end of summer. Since they are the same size as adults in the juvenile stage, you will not know which one is the juvenile unless you pay attention to the subtle differences, such as lighter colored plumage or differences in voice, which mostly disappear during autumn.

Fortunately we could easily distinguish the Grey Heron, the largest of the herons, from the others. Among large birds, some take 2 to 3 years to reach maturity, so it is easy to identify juvenile birds.

Mr. Anzai gave us a hint, saying, “Adult Grey Herons have a bluish tinge to the grey coloring on their back but a juvenile doesn't have the bluish tinge.”

With that in mind, we observed the birds carefully, eliciting a variety of comments, such as

“That one is not very beautiful so it's a juvenile, right?”,

“The crest that looks like a topknot coming out from the back of the head is short!” and “It might not be as good at catching fish as an adult.”

Here we took a break at the Yatsu-higata Nature Observation Center. The facility is very spacious and there is a well-organized exhibition area that provides information on the structure of the tidal flat and the creatures that live there. The restaurant in the center faces onto the water, and pairs of binoculars have been placed on the tables here and there for visitors to use.

The basement-level observation space puts visitors almost eye-level with the water's surface where they can enjoy a 180-degree panoramic view of the tidal flat. Visitors can also enjoy using the binoculars, telescopes, and bird photo guides set out in the space.

On the way back from the observation center, we discovered young Brown-eared Bulbuls in a tree along with the trail. Their parent carrying back food was alarmed by our presence and fly away, but the juvenile birds, which were not even two meters away from us, sat calmly on their perch and were joined on the branch by four of its siblings as we were watching them.

This was a little late in the season to observe birds at the stage of development when the tail feathers had not yet grown in and you could tell at first glance that they were young birds. Since there was a lot of rain this year before the heat came, there were fewer insects than during the normal breeding season, so breeding may have been delayed.

Since they look small if their tail feathers are not fully grown, on top of being easy to identify, they were very cute. According to Mr. Anzai, their tail feathers would probably grow in within the next 2 or 3 days, making it harder to distinguish them from the adults, and we would not be able to get so close to them because they would become more alert to danger. It seems we were quite lucky to see them today.

Although we observed many things, it felt as if the adage in the bird watching world that “birds are few in summer” rang true for us today and we did not see many species of birds.

However, Mr. Anzai told us that it was the complete opposite.

“Within the year, the number of birds in August may be among the highest. That's because even though the singing has stopped and the birds no longer stand out after molting, we could see young chicks like the Brown-eared Bulbuls chicks that we just saw since they hadn't become prey to other animals.”

Each year birds continue to raise broods of many chicks but, unlike humans, they never have overpopulation. In the natural world where many creatures become food for other creatures, a low survival rate is not surprising. Considering birds that are able to survive their first winter and breed in the next year, the number of young birds that get through the migration in autumn and the hard winter to be able to breed in the spring must be very few indeed. It may be that “birds are few in summer” since there are few people out bird watching in the heat of summer in the first place.

Mr. Anzai was also surprised to find out that the migration of sandpipers begins in August as he had long ago heard that sandpipers migrated in spring and autumn, but it seems that he has memories of them passing through tidal flats in the extreme heat. Enjoying the coolness inside the facility, he talked about being able to observe sandpipers thanks to the construction of such places as the Tokyo Wild Bird Park and the Yatsu-higata Nature Observation Center, noting how “it's quite a change from the old days.”

Eastern Spot-billed Ducks, Northern Pintail, Great Cormorant, Common Sandpiper, Grey Heron, Great Egret, Mongolian Plover, Intermediate Egret, Little Egret, Black-necked Grebe, Little Grebe, Grey Plover, Grey-tailed Tattler, Common Greenshank, Black-tailed Gull, Brown-eared Bulbul, Japanese White-eye, White Wagtail, Rock Dove, Eurasian Tree Sparrow, White-cheeked Starling, Barn Swallow, Birds confirmed only by their voice: Azure-winged Magpie, Large-billed Crow