Unraveling the mysteries of birds vol.4

Why do migratory birds migrate?

Uncover the secrets of birds that migrate long distances.

Uncover the secrets of birds that migrate long distances.

Where do the many swallows that we see in summer and the many ducks

that we see in winter come from, and where do they go?

swallows and ducks are “migratory birds,”

which means they travel to and from faraway places every year in spring and winter.

Why do they travel to and from those faraway places? Don't they get lost? How do they get food along the way?

Let's uncover the amazing secrets of migratory birds!

Challenge #1

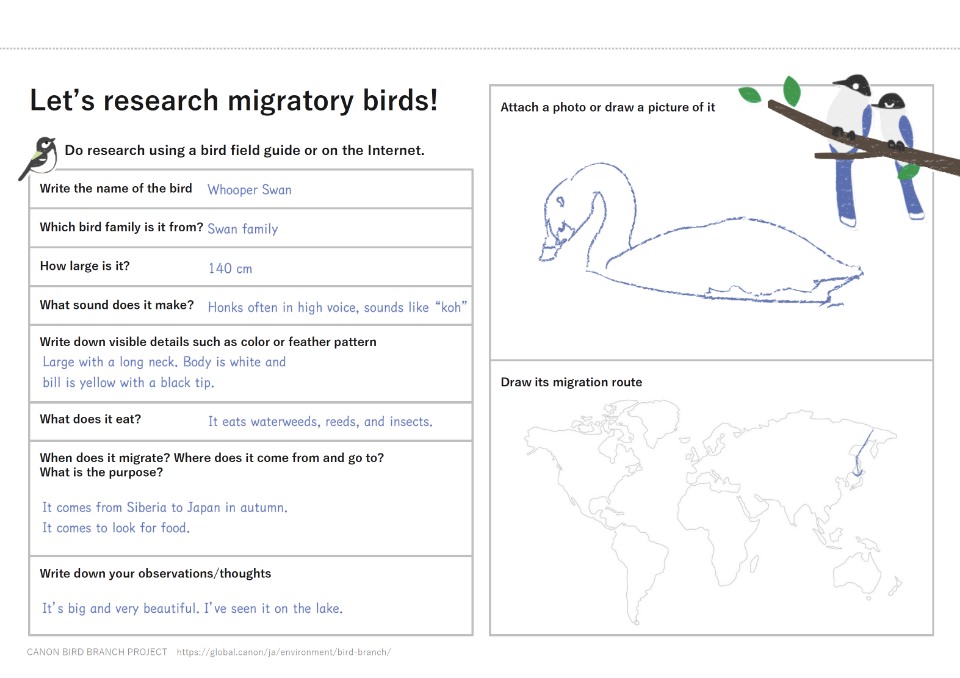

One reason birds migrate is for food. For example, when winter comes, water birds such as swans and ducks, and small birds such as the Naumann's Thrush come to Japan from Siberia. Birds that come to Japan to spend the winter are called “winter birds.” Water birds that live on the surface of the water and small birds that search for food on the ground cannot survive in northern places on the continent that become covered with snow and ice. It is believed that winter birds migrate to the warm places of Japan in search of food.

On the other hand, there are also birds that come in summer called “summer birds.” In Japan, the Barn Swallow comes to urban areas, and small birds that are beautiful both in appearance and song, such as the Blue-and-white Flycatcher, the Narcissus Flycatcher, and the Black Paradise Flycatcher, come to forests. The purpose for summer birds is to raise their young. In countries with a temperate climate, insects become plentiful for a short period when summer comes. Birds that eat insects, such as Barn Swallows and Blue-and-white Flycatchers, can get enough food to raise their young hatchlings. Since flying insects become scarce when winter comes, both Barn Swallows and Blue-and-white Flycatchers leave Japan and migrate to warmer southern regions.

Birds such as hawks, owls, and the Peregrine Falcon, which have a sharp bill and claws and eat other animals, are called birds of prey or raptors. Migration for the purpose of finding richer food sources is not limited to water birds and small birds. Raptors such as the Grey-faced Buzzard-eagle and the Oriental Honey Buzzard also migrate.

The summer bird Grey-faced Buzzard-eagle is a hawk that lives in secondary forest areas (forests that border agricultural land) of Japan and feeds on frogs, snakes, and large insects. Similarly, the Oriental Honey Buzzard also attacks the hives of honeybees and wasps to eat the larvae or pupae. The small animals that they prey on hibernate in winter and no longer serve as a food source. Because of this, the Grey-faced Buzzard-eagle and the Oriental Honey Buzzard migrate south to the islands of Indonesia to spend the winter, returning to Japan when spring comes. From satellite transmitter data we understand that the Grey-faced Buzzard-eagle and the Oriental Honey Buzzard take different migration routes in spring than they do in autumn. It seems probable that they choose the migration route according to weather patterns and other climate conditions as well as prevailing wind currents.

Challenge #2

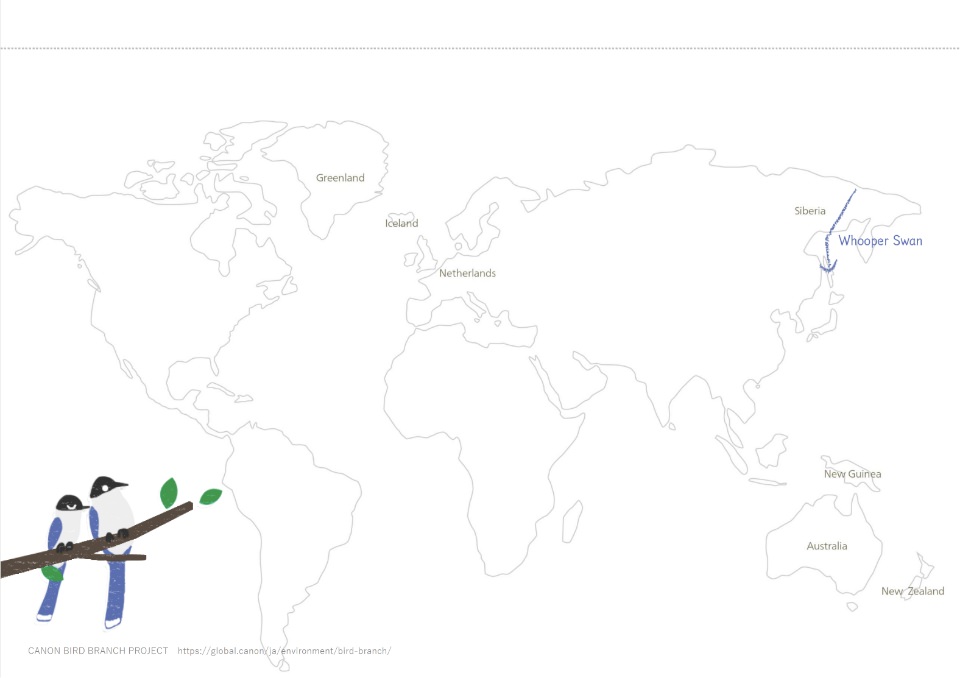

Migratory birds sometimes cover distances of thousands of kilometers on their migration. For example, some species of sandpiper and plover that raise their young in Arctic regions of Siberia and Alaska in the Northern Hemisphere migrate to Australia and New Zealand in the Southern Hemisphere to spend the winter.

A Far Eastern Curlew fitted with a transmitter flew 3,000 kilometers non-stop from New Guinea to the mouth of the Yoshino River in Shikoku, Japan, after taking a brief rest along its migration route from Australia.

Among the many birds that migrate long distances, the one that travels the farthest distance is undoubtedly the Arctic Tern. It has the longest yearly migration among birds, traveling between the Arctic and Antarctica. The Arctic Tern, which raises its young in Iceland and Greenland, migrates southward over the Atlantic Ocean in a large ‘S' pattern to settle for some time around Antarctica and then gradually heads northward back to the Arctic region.

It is understood that the average distance covered yearly for birds with that migration route is 70,900 kilometers, and for the group that raises its young in the Netherlands, the migration circuit amounts to 90,000 kilometers. If an Arctic Tern lives for 30 years, it will log about 2.4 million flight kilometers in its lifetime. That is a distance equivalent to traveling from Earth to the Moon and back three times.

As spring—the season for raising young—gets closer, the daytime gets longer. Birds sense the increasing length of day and start preparing for migration. The light that comes in through a bird's eyes is a signal that is transmitted to the brain, and the brain then triggers the release of reproductive (mating) hormones. The action of these hormones causes birds to start feeling restless somehow before the migration. It is hard to understand unless you are a bird, but they start to get a feeling something like “I have to head north” or “I must start flying….” When autumn comes and the daytime becomes shorter, the reproductive hormones stop being released, and birds start preparing to travel south.

Challenge #3

Many sandpipers and plovers migrate long distances from the Arctic region to destinations in the Southern Hemisphere. Along the way, some bird species make a stopover to feed for a while at tidal flats or other feeding grounds, but there are others that fly straight to their destination, making very few if any stops. For example, during its autumn migration a Latham's Snipe fitted with a transmitter in Japan flew 5,000 kilometers to New Guinea over six days without stopping. Similarly, a Bar-tailed Godwit fitted with a transmitter in Alaska flew 12,000 kilometers non-stop across the Pacific Ocean in 11 days. It did not sleep or eat anything during that time.

By recording position data at set time intervals while a bird is flying, we can find out the speed the bird flew at between two locations.

The Wild Bird Society of Japan attached a satellite transmitter on Latham's Snipes in Hokkaido to investigate the migration route and number of days it takes them to fly to Australia. This year, one of the birds fitted with a transmitter from the Yufutsu Plain in Hokkaido arrived at its wintering area in Australia after flying the 7,800-kilometer distance non-stop in six days. It was calculated to have flown at a speed of about 50 km/h.

The Bar-tailed Godwit has an even more impressive record. A Bar-tailed Godwit flew 12,000 kilometers across the Pacific Ocean from its breeding grounds in Alaska to its wintering spot in New Zealand in 11 days without stopping even once. Its average speed enroute was about 45 km/h.

Sandpipers and plovers fatten themselves up well before starting their migration. Depending on the species, some birds are known to double their weight. Burning the fat bit by bit, birds migrate long distances without stopping, and when they arrive at their destination, they appear to have lost half of their weight.

Are they all right though without sleeping for a week or 10 days? For example, relatives of the Pacific Swift spend most of their life during the year in the air, but we understand that they also fly at night and seem to sleep while flying. Since dolphins and other animals are known to be capable of operating the left and right hemispheres of their brain independently, enabling them to put one side of their brain to sleep and then the other, perhaps birds migrating long distances may also alternate resting the right and left sides of their brain while flying.

Challenge #4

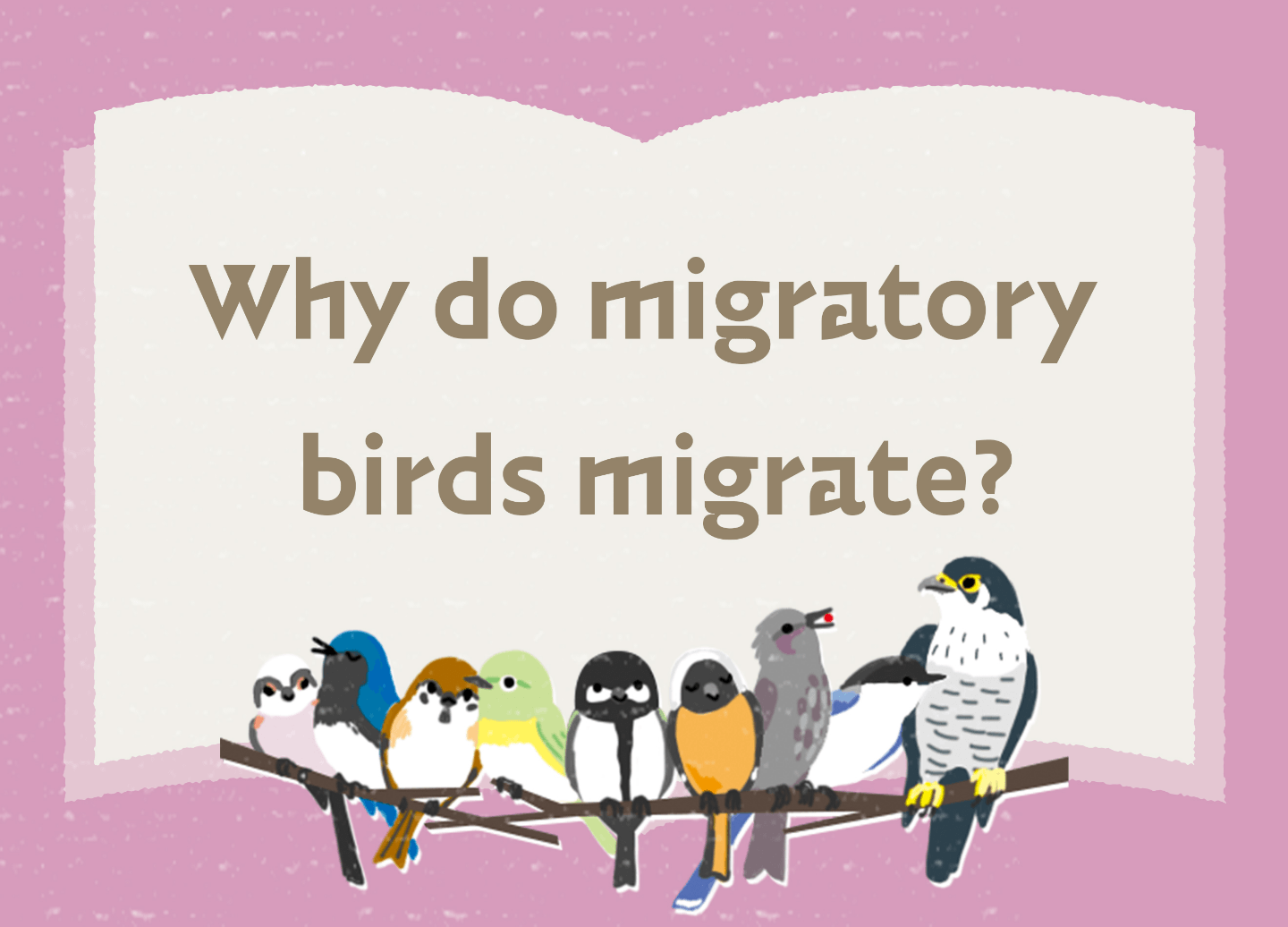

Migrating birds can determine their bearing (compass orientation) by the position of the Sun. The Sun rises in the east and sets in the west. Birds have an internal clock and know how much time has passed since sunrise, so they know the direction of east, west, south, and north based on the time of day and the position of the Sun. This navigational ability that birds have is called a “sun compass.”

So how do migrating birds navigate at night? We understand that birds migrating in the night look at the position of the stars. Researchers in North America investigated this with an experiment, taking an Indigo Bunting in a cage to a planetarium around the time for its migration to start. They recorded the direction the bird faced and flapped its wings as they moved the position of the stars in the night sky.

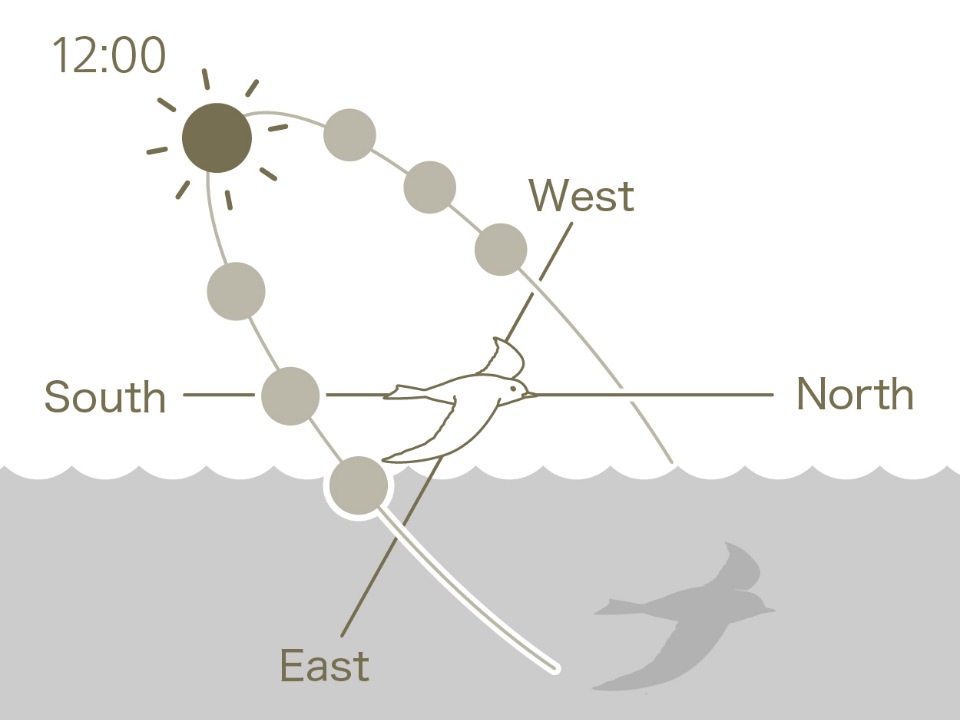

How do they navigate when it is cloudy and they cannot see the stars at night? Even if it is cloudy, birds do not mistake their direction. That is because birds are sensing magnetic forces. The Earth is like a large magnet, and its magnetic field runs in a north-south direction. Birds are said to sense magnetic forces that humans cannot and that is how they can determine their direction during migration.

No matter how exceptional the abilities of migratory birds are that enable them to overcome various tight situations, migration is without a doubt an arduous and dangerous undertaking. This is so especially for young birds that have just left the nest that year on their first migration. Swans, geese, and cranes journey together as a family group, so young birds fly to their destination with their parents. Other birds likely also do the same and fly alongside adult birds.

It is hard to know for sure since there is no data to confirm but it seems likely that some birds die along the way because of being separated from the flock, getting caught in a typhoon, or occasionally falling victim to birds of prey such as the Peregrine Falcon. Year after year birds complete their migration circuits. In spring and autumn, and when looking up at the night sky sometimes, let's pray for the safe journey of migrating birds.

Fill in the worksheet and complete the bird migration world map based on what you learned about the migration routes of birds around the world while reading this column.

Wildlife ecologist

Professor Emeritus, College of Science at Department of Life Science in Rikkyo University

Former President of the Ornithological Society of Japan

Born in 1950 in Osaka Prefecture. Areas of research include evolutionary ecology of plants and animals with particular focus on avian species, and also environmental issues. Vice-president and Trustee member of the Wild Bird Society of Japan. Currently works as editor in chief of Strix, a member-authored journal of field ornithology, published by the Wild Bird Society of Japan.