Hiroshi Nomura is a fixture in photography, contemporary art, publishing, and other creative scenes.

After serving as a judge for the 2020 (43rd edition) New Cosmos of Photography,

he gave a lecture on photography at the 2020 New Cosmos of Photography Exhibition.

His lecture provided insight into the process he goes through to form his ironic works that have charmed and captivated so many viewers.

Nomura also discussed his ideas and their sources, while presenting slides of his work, ranging from his Excellence Award-winning work through to his newest works.

Nomura was interviewed by Takashi Kakishima, owner of Poetic Scape, a Nakameguro gallery.

Kakishima:We go back a long time, and you've exhibited a total of seven times at our gallery. Today, I'd like to talk to you about your career, especially your photographic works, beginning with the award you won at the New Cosmos of Photography, a contest you discovered while attending the Tokyo University of the Arts.

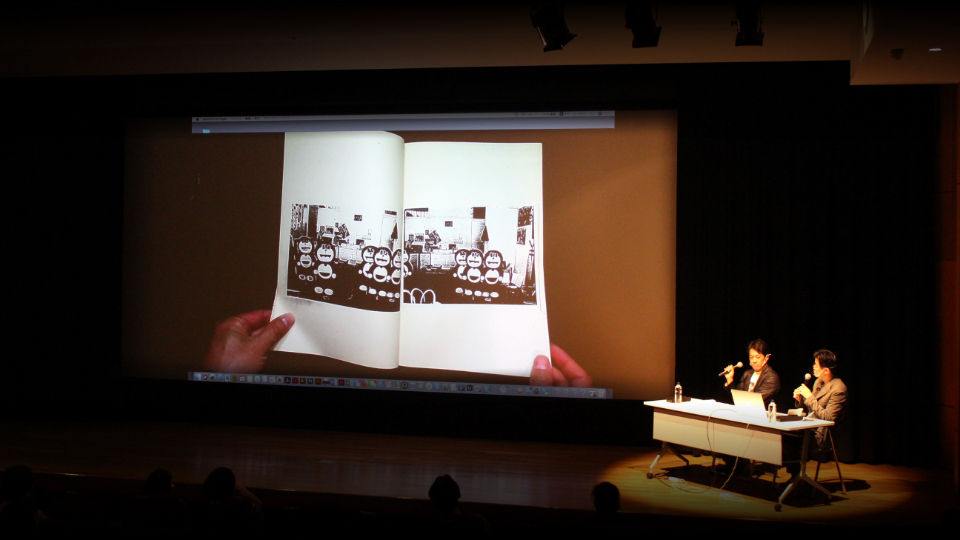

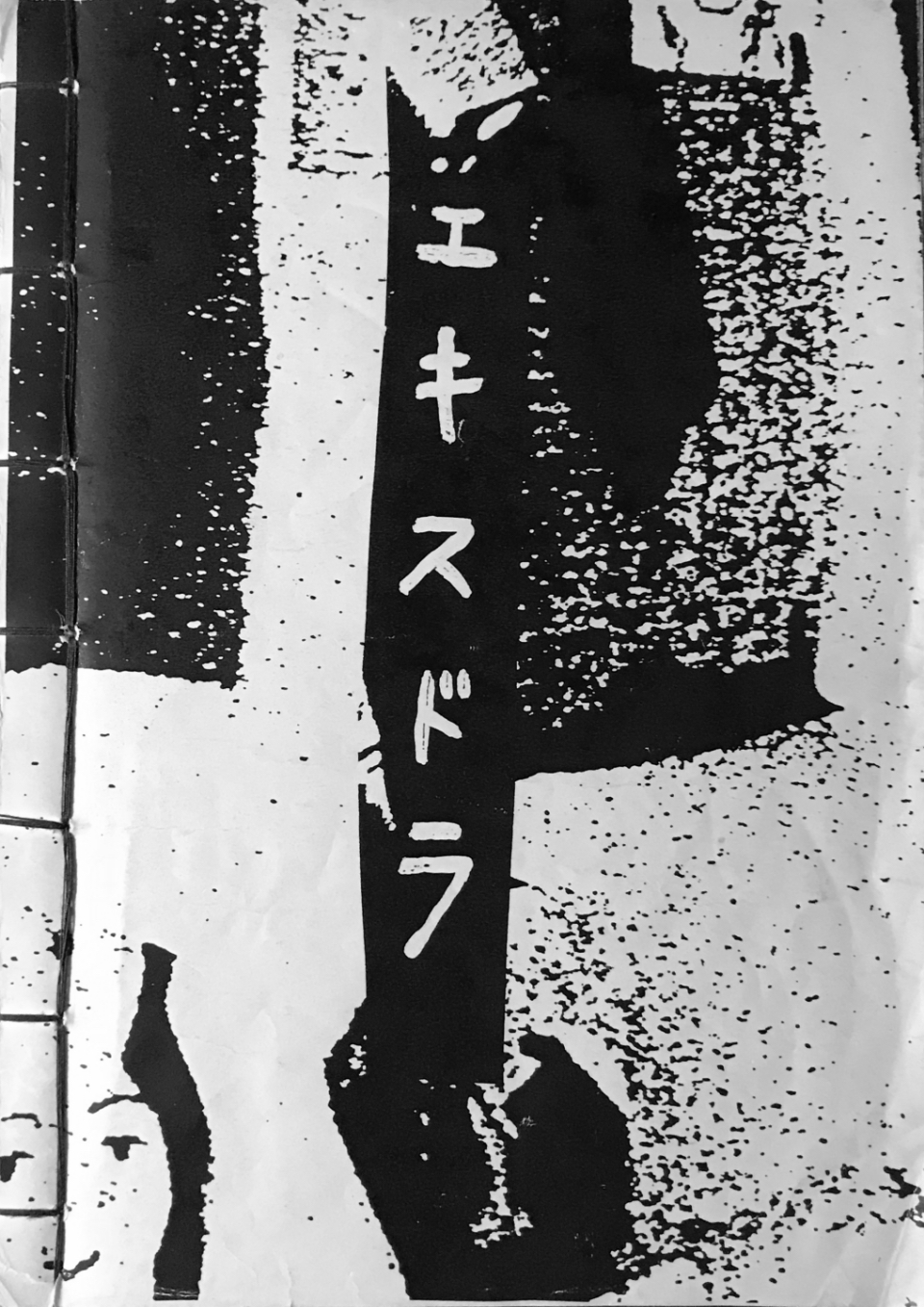

Nomura:The New Cosmos of Photography was held four times a year back then. I happened to hear about the contest when I was an undergraduate, and I submitted Exdora for the first contest and Doranquilizer for the second. My intent was to show my work in a somewhat coherent fashion for critique at my university. I ended up creating both books on convenience-store photocopiers. Photocopies in those days were of poorer quality, rougher, and had harsher contrast than now. The characters I drew on the photos had a unusual vibrancy about them, which engendered a bizarre reality. The incongruity and oddity of the work I created struck a chord with me and led me to believe that it might actually be a work of photography.

Kakishima:Launching a contest called “New Cosmos” at the time gave a palpable sense of possibilities. It's still provocative in its way even today. It's also interesting that the judges back then were so receptive.

Nomura:At the time, I didn't even understand what the word “photo” in photography meant, but I nevertheless felt that the finished book, although lacking any photographic quality, had something about it that couldn't be laughed off easily. From the outset, I decided to enter the contest five times.

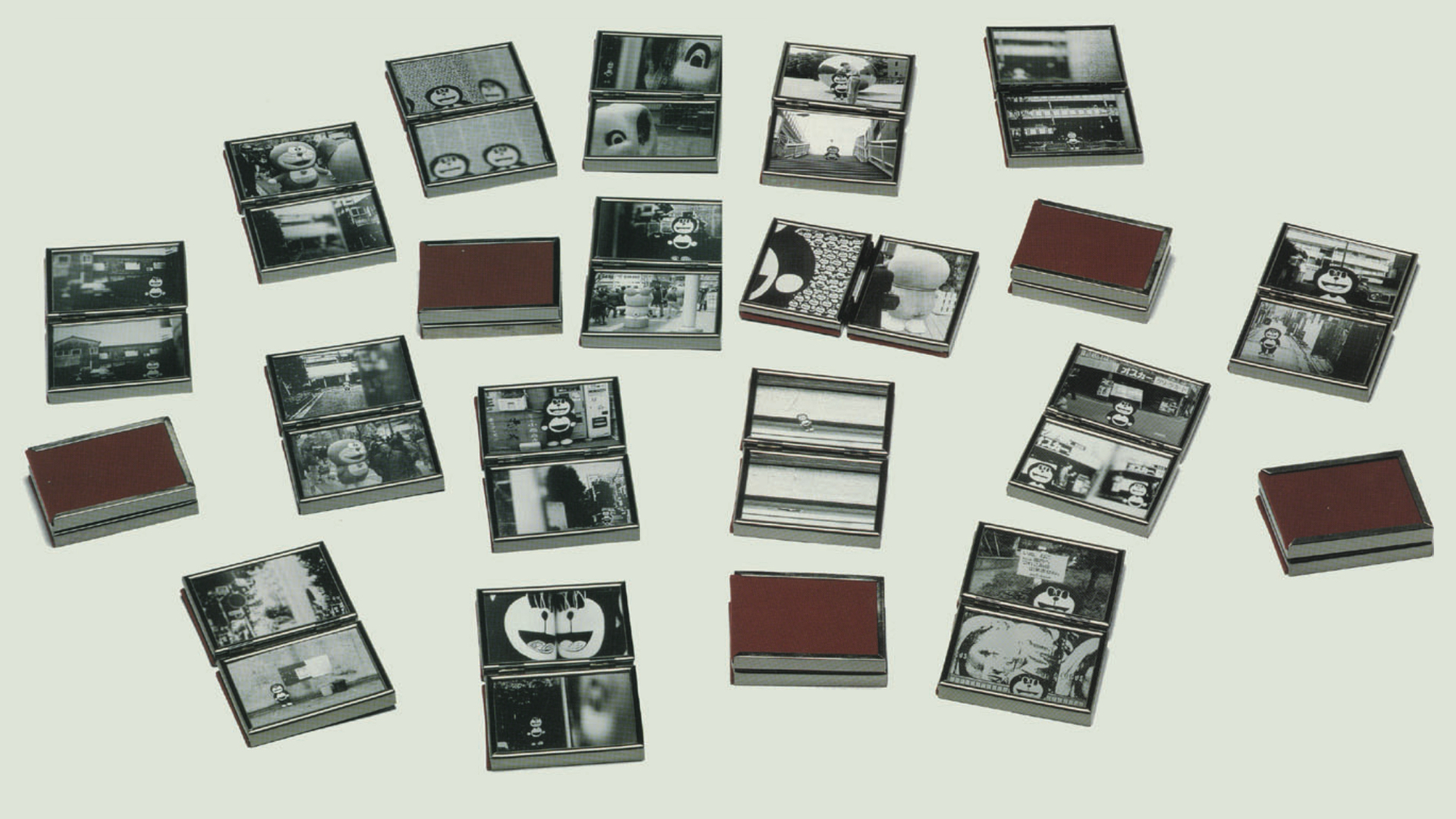

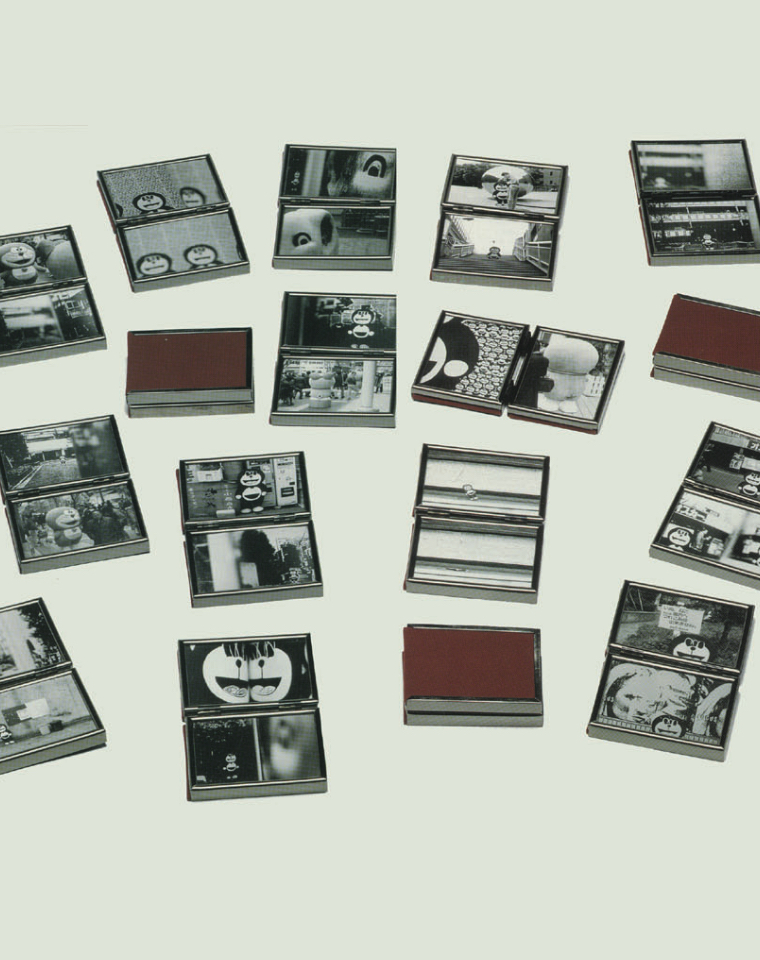

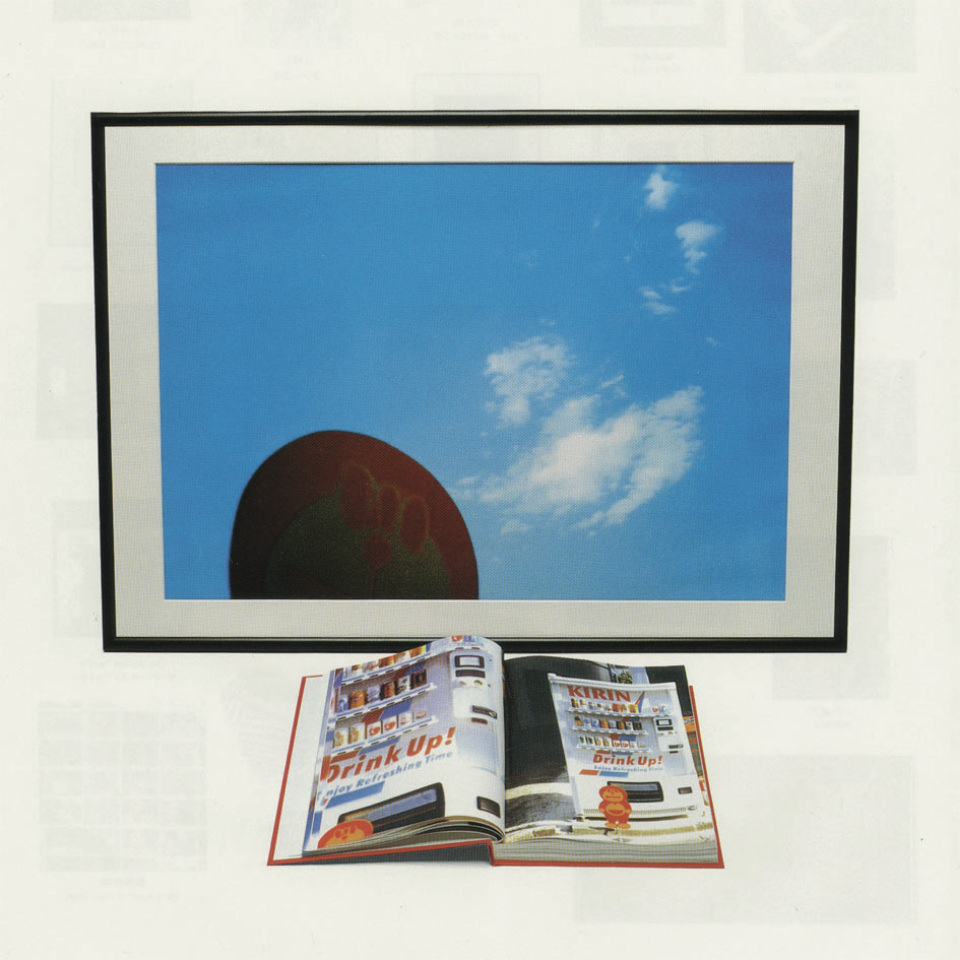

I was greatly encouraged when I received honorable mentions in both the first and second contests. Entering my work in the contests pushed me to study photography, which was another positive outcome. I was given an Excellence Award at the third contest for a work that resembled a treasure chest made of velvet material, where you opened small frames folded in half to see the photos. My entry for the fourth contest was terrible, but I won my second Excellence Award at the fifth contest for a book constructed from color photocopies. The title was Drink up. The photocopies had very coarse toner particles, and the images had this unclear visage to them. One of the photos was of a vending machine that had “Drink up” written on the side, so I chose that as the title.

Kakishima:What were you thinking back then while making these works? The Straight Photography movement was starting to enter the mainstream in the mid-90s, and the New Cosmos of Photography had become known as an important gateway for up-and-coming photographers.

Nomura:Straight Photography was at its zenith at the time. While the movement garnered some reaction, it feels like a footnote or poor imitator in the general arc of photography. My Excellence Award-winning work from the fifth contest was exhibited at the second New Cosmos of Photography Exhibition in 1993. It was around this time that the contest gained its reputation as a pathway to a successful career. 1994 saw Hiromix win the Grand Prize, and Masafumi Sanai came on the scene. The girls' photo phenomenon was a hit too. Outside of Japan, in 1997, you had Larry Clark making a name for himself. A more open style of photography emerged that marked a sharp contrast from the old Japanese style of photography that seemed dated and from the rigid conceptual photography of contemporary art. It was inevitable, or at the very least refreshing, that this style of photography would become a part of the art scene.

Exdora

Drink up

Kakishima:Not long after this, you held a solo exhibition at the Taka Ishii Gallery (Otsuka, 1997).

Nomura:It was my first real solo exhibition, a sort of career high for me personally. I created and exhibited works constructed from both drawings and photographs. I was working at the time in a design office led by a bookmaker named Satoshi Machiguchi. I graduated in oil painting and had no experience in design, but he asked me to be his assistant, which I did for two and a half years.

Then came the year 2000. Some called the decade the “noughts”, and in many ways it was a nought for me too. But things felt like they started to move ahead slowly after publishing Eyes (AKAAKA Art Publishing) in 2007. I was in a major slump for the previous seven years, just managing to scrape by. But throughout this period, I always thought that my work was interesting, although that may just be conceit on my part.

Kakishima:It's certainly important to believe in the worth of your work, even if no one else is applauding it.

Kakishima:For The Photograph: What You See & What You Don't #02 (University Art Museum, Tokyo University of the Arts, 2015), you exhibited a work centered on an insect you named the Phyllium Rayograph [replicated leaf insect]. A couple at the exhibition who saw your work were heard saying: “The world sure has some really weird bugs”.

Nomura:That makes me feel incredibly guilty. [laughs] Photography consists of the processes of developing, stopping, and fixing. But as an experiment, I looked at these processes from a different perspective. I wondered what printed photographs would be like if insects like these existed. From there, I tried to fix images with a luminescent sheet cut in the pattern of a Phyllium Rayograph. It has a slight sheen, but it is just a dead leaf — a fake for illustrative purposes. An insect appears to be there, but I simply combined dead leaves and sprayed them with a luminescent spray. When you hold it up in the dark, it looks like it glows.

Kakishima:That's the photographic artifice of fixing the shadow of something in a certain place. Your work may seem simple, but it consists of many elements arranged in multiple layers. Some are gimmicks, some are fantasies. Or they may even be a fictional setting in which insects called the Phyllium Rayograph exist. However, even after the secret is revealed, there is still something about the work that leaves you feeling a bit bewildered and unsure. I guess that is the beauty of your work. I think many of your works bring back something that can't be fully expressed in words. Are you conscious of this?

Nomura:Of course, I am aware of this. Having something that cannot be reduced to something else is important. Having something that cannot be communicated is important. Photography is about giving the impression that you have seen something when in fact you have not fathomed it. Things that are immediately apparent when you look at them are quite different from things that take time to come into focus. That is the power inherent in photography. I'm clearly just on the sidelines of all of this, but I want to incorporate the ominous nature of photography. I want to incorporate this nature and demonstrate that it exists. I believe this is my role. I sometimes feel guilty toward photography even as I create photographic works. It feels like I'm doing something I shouldn't be doing, even though I am performing the act of photography. So when someone confronts me and says “This is wrong”, I have no choice but to concur. Nevertheless, I feel this is the only place from which I can speak; I can't stand in the middle.

Kakishima:In a way, you have a lot of respect for Straight Photography.

Nomura:I think Straight Photography is the best. I see it as the noble path. If you try a lot of things and became skilled at them, then you might be able to take interesting photos, but that's not me. That's why the photos I like and the photos I make are different. Even if I wanted to become a photographer because I like a certain photographer's work, that work is what that artist does, and it will always be different from what you do and what you shoot. I realize some people repeat their means of expressions and themes, and that's something I'm conscious of every time I create something.

Exhibit of Phyllium Rayograph

Kakishima:You put out a book called Slash (2010). It's an odd book printed on flimsy paper.

Nomura:That book consists of images cropped from Google Street View. I manipulated the photos to have a snapshot feel. I actually used a half-frame camera for Exdora. For Slash, I crafted the images to look as if they had been cropped to half-frame size. The images were printed on thin kraft paper, like the paper used for wrapping in department stores. It's a material that could be from anywhere, and it has a quality that isn't associated with any specific country. I traversed across many different countries on Street View and chose images. Slash is a far cry from my usual style, but it's been surprisingly popular. I converted the data to film and then I made and framed platinum prints from the film.

Kakishima:So you wandered around the world on Street View on your computer screen without stepping foot outside your house.

Nomura:Whenever I found a place I liked, I made a rough capture of it and then cropped it. Eventually, I would crop it to a half-frame perspective. Street View now has high-resolution images,

but back in around 2010, the resolution was equivalent to a half-frame print. I processed the images to get the monochrome effect. What was really curious to me as I did this was I got the sense that I had been to the place in the photo and I felt like congratulating myself on taking a good shot. This is probably a projection of the desire within me for Straight Photography, and, although indirect, the images have the feel of analog snapshots passed through the digital domain.

Kakishima:It was interesting to me that viewers, on seeing the grainy monochrome prints, would automatically assume the prints were so-called works of art or artistic photographs and they would look at your work according to that common codification. It's a testament to your work that people aren't turned off as soon as they find out the images are from Google Street View. If you think deeply about where, in terms of the essential act of photography, the difference lies between wandering around Street View, capturing images, and developing them into prints and actually walking around the same streets and taking shots, everyone will leave feeling light-headed. The work harbors the question — even if not posed explicitly — of how does the medium we call photography become a photograph.

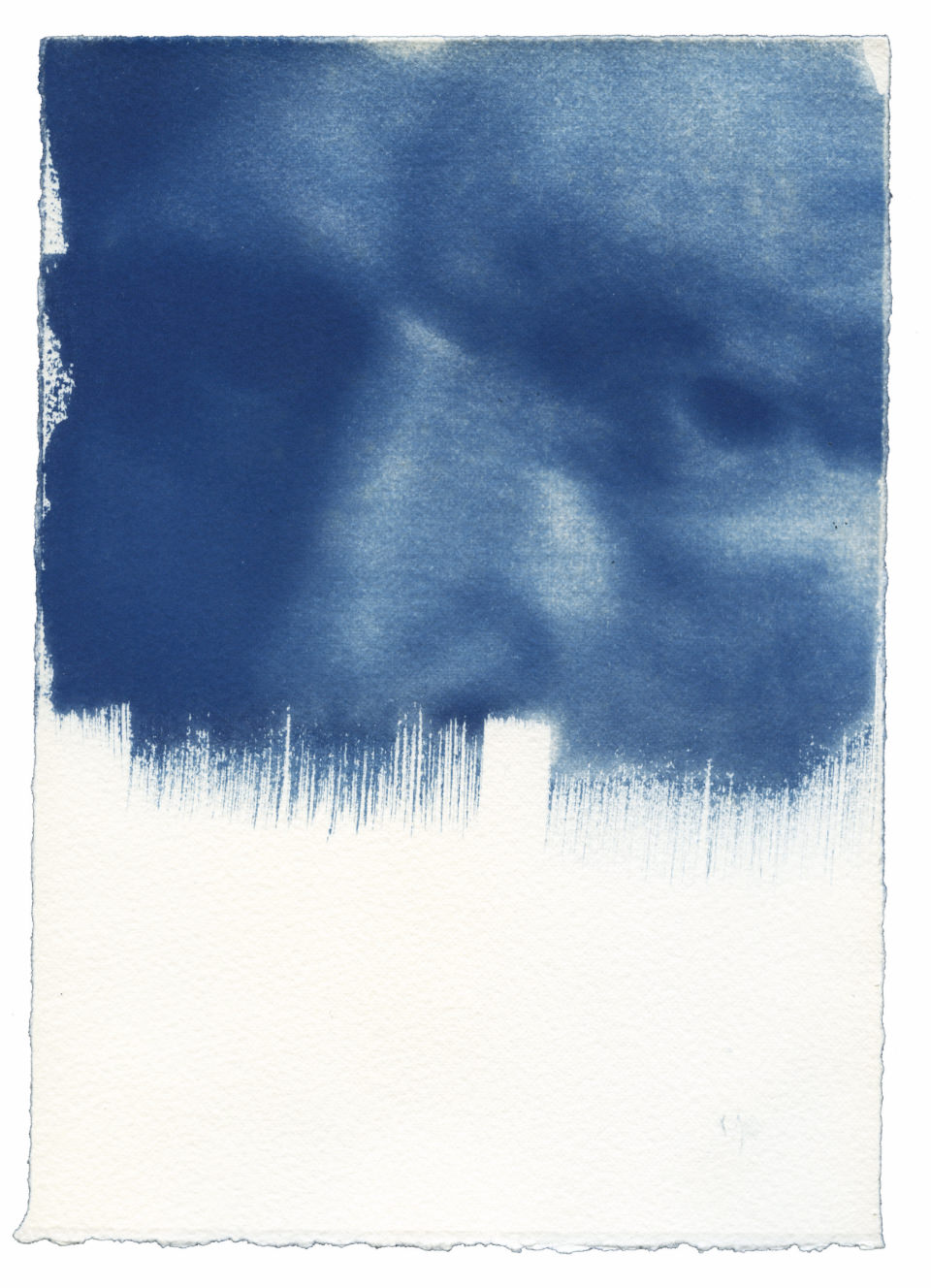

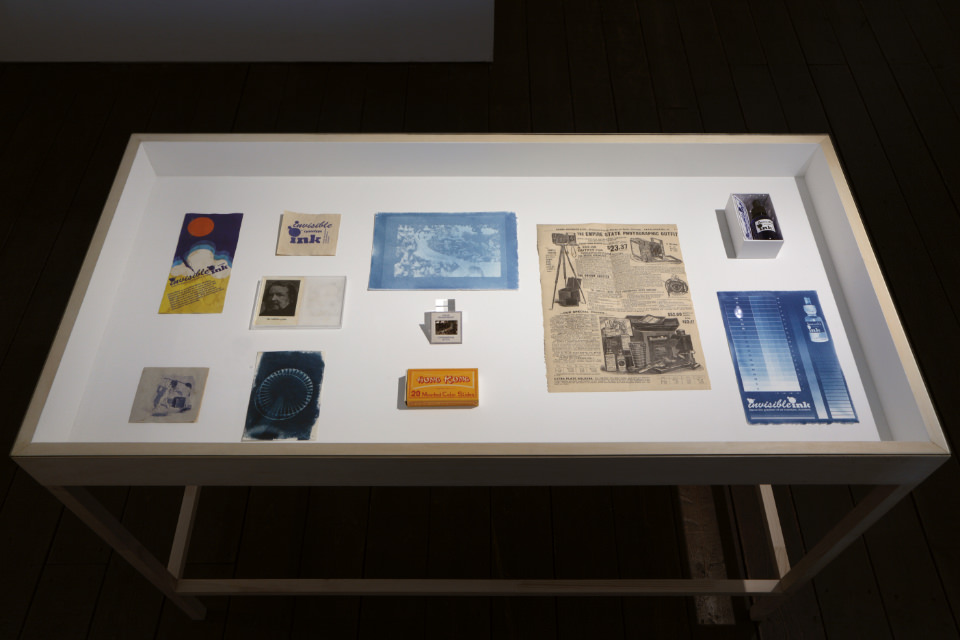

Nomura:In 2016, I created a work from imaginary magic blue ink called “invisible ink”. It consists of photos of Van Gogh's famous self-portraits. Van Gogh's self-portraits emphasize the materiality of the paint, which, together with his unique touch, creates his facial expressions. I took out-of-focus shots of Van Gogh's self-portraits and developed them with my “invisible ink”. The result makes it appear as if Van Gogh is observing at his own face looking through a mirror. The goal was to conjure up a photographic image by hiding the brushstrokes in the paintings. This is what was meant by using “invisible ink” to create the images.

I added the subtitle: “A collaborative work based on Van Gogh”. The bottle is just an empty blue bottle, with no “invisible ink” or anything else in it. I included an old pamphlet on invisible ink that described how it was developed and a portrait of William Lewis, the man who invented invisible ink.

Everyone examined the images closely, but when they did, I again felt guilty and apologetic, so I didn't have the heart to tell them that it was all fake. Some people came, looked around, and then left, saying “I guess the ink's not for sale”.

Kakishima:You crafted a reality in which invisible ink as a product had been discontinued, but the grandson was bringing it back and had collaborated on the new product launch event with the artist Hiroshi Nomura. It became an exhibition with the widest variety of contexts and quotes I've ever seen. You even located the company that developed the ink in Argleton, England, a place that does not exist. What I think you do so well in setting up these contexts is that, as with William Lewis, you don't simply make things up from scratch but instead cleverly pull in things that actually existed. As people familiar with the Internet may know, someone a few years ago discovered a place called Argleton marked on Google Maps in a nondescript field in the middle of rural England. The non-existent town became a viral sensation, with people organizing tours to Argleton and selling Argleton t-shirts. You repurposed this context — that an Internet bug created an impact in the real world — for your work. I feel many of your works take place in the gaps between reality and fantasy.

Nomura:My works are fabrications. [laughs] These fabrications change the way you look at things, or maybe the way you perceive things.

Van Gogh's self-portraits

invisible ink

invisible ink

Kakishima:Another project you took on was reorganizing the vast camera collection at the Yokohama Civic Art Gallery Azamino from the perspective of an artist while you were a guest curator there. You created an exhibition using cartoon strips that you drew and photographs. The exhibition even travelled to China.

Nomura:In 2011, when there was a lot going on that made me think about digital versus analog and the earthquake disaster, I wanted to experiment with something that people would enjoy. So I started drawing and posting three-frame cartoons on social media that had to do with photography and related topics. The cartoons were so well received that I kept doing them, and when I had accumulated quite a few, I put out a book called CAMERAer. Because of this, I was asked by the Yokohama Civic Art Gallery Azamino if I would supervise an exhibition of their camera and photo collection. Later on, they asked me to curate the exhibition. Since I also do graphic design, I said, “Let me do the flyers. I'll also design the exhibition space. And I'll design the outside banners too.” It became like my own solo exhibition. When the people at the A4 Art Museum in China saw it, they said they would love to host the exhibition with the inclusion of Chinese artists. I also received the 31st Society of Photography Award that year. I felt a lot of guilt for winning the award for drawing cartoons. It's now been almost exactly 180 years since photography was invented, right? I attempted to connect past and present artists through cartoons and bring out the potential of their respective photographs. It was a great experience, made all the better because it was truly interesting.

“THE DARK and BRIGHT ROOM of CAMERAer,”

an exhibition of photographs in the collection of Yokohama City

(Yokohama Civic Art Gallery Azamino)

Nomura:I released Merandi in 2020. The concept was to mimic in paintings the eye photos from my Eyes collection. My views about paint changed after passing once through the medium of photography. I conceived of Merandi as something that took the form of paintings both through paint and through Eyes, which had become a medium equivalent to paint.

I'm not sure why I ended up doing this, but the motivation for my first work, Exdora, already had elements of two-dimensional works (paintings). When I look back at the work now, there were so many areas that were not clear at the time. Although I thought it was good, I find the dated issues and concepts of the work to be immature. People often suggest to put your concept into words, as if by making the parts that are not clear, you can understand what you are creating. But what you can put into words at any given time is very limited. There are also so many things that cannot be verbalized in your first works, and I think the act of unpacking these things, of pursuing certain kinds of solutions in different forms, ultimately becomes the act of creating art. That's why I'm kind of glad that I didn't receive too much praise early on. Over the past decade, including my work with you, I feel I've been reshuffling the immature cards I'd been holding on to and then drawing out a card. Each time I do this, I check to see how the card was and what it looks like, after which I create and present the card in its altered form, and this is the result.

Kakishima:You've worked hard with an awareness of your own position and an indefatigable spirit. The New Cosmos of Photography kick-started your early career and it's wonderful that its central concept is what can be done in photography. In the sense that it gave you that courage, the New Cosmos of Photography occupies a very meaningful place. Some people who visit our gallery have strong opinions on what photography should be and even claim that a certain exhibit is not photography at all. But I think that photography is stronger than we give it credit for; photography collaborates well with other genres and it even has the potential to swallow other genres, if they should be so unlucky. I feel you are here today because, even though there may have been times when you were down on your luck, you persevered without regarding yourself as being unfortunate.

Nomura:What can I say when I'm told I'm unfortunate … [laughs]

Kakishima:It means you don't believe you were ever unfortunate, and that's the most important point. [laughs]

Nomura:When someone compliments your work, their words soon fade from memory. But when someone bashes your work, the feeling you have of “Why don't they understand” sticks with you forever. Such criticism becomes my motivation. Even things that appear to have been resolved still persist in my mind. Maybe that's why now I don't seek out praise.

— Thank you very much.

「Merandi」(2020年2月22日(土)~4月4日(土)、POETIC SCAPE、東京)

Hiroshi Nomura graduated from the Graduate School of Fine Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts with a major in Painting in 1995. While a student,he produced a large number of works in various media, focusing on photography. Recently, he created a comic book, “CAMERAer,” about cameras and photography (published by go passion in 2019). He was a guest curator of “THE DARK and BRIGHT ROOM of CAMERAer,” an exhibition of photographs in the collection of Yokohama City (Yokohama Civic Art Gallery Azamino), which then became a traveling exhibition, shown at the A4 Art Museum in Chengdu, China (until February 23, 2020). His solo exhibitions have included “EYES GOODS” (2008, LOGOS Gallery, Tokyo), “Slash/Ghost” (2014, A-things, Tokyo), “Doppelopment” (2017, POETIC SCAPE, Tokyo), and “Merandi” (2020, POETIC SCAPE, Tokyo). He has also exhibited artworks in many overseas shows, such as “PHOTOESPAÑA 2012 Asia Serendipity” (2012, Spain) and “Belfast Photo Festival” (2019, Northern Ireland). His major publications include “EYES” (2007, AKAAKA Art Publishing) and “Slash” (2010, N/T WORKS). He won the Excellence Award at the 3rd and 5th Canon New Cosmos of Photography Competitions, in 1992 and 1993, and was awarded the Society of Photography Award in 2019.

Takashi Kakishima is the founder and director of Gallery POETIC SCAPE.

Since its opening in 2011, he has curated a number of exhibitions of both established and emerging artists, including Daido Moriyama, Hiroshi Nomura and Toshiya Watanabe. He has also been a part-time lecturer at Kyoto University of Art since 2017.