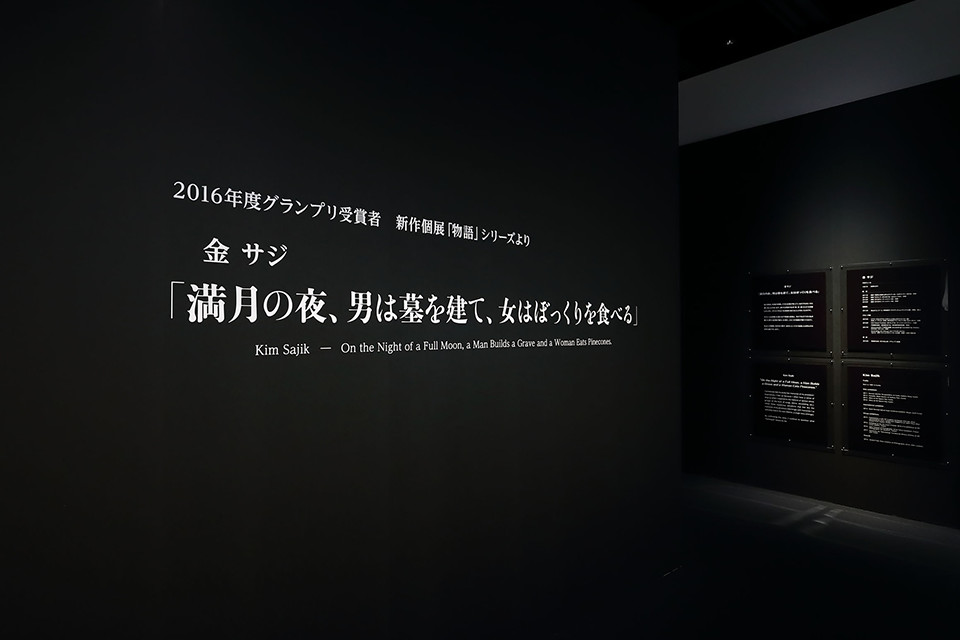

Grand Prize winner of the 39th public competition in 2016 for Story.

Japan and Korea: Kim Sajik explores her roots and produces works in a powerful style that seem to untangle them. What is the story behind her solo exhibition of new works, The Night of a Full Moon, a Man Builds a Grave and a Woman Eats Pinecones.

We spoke with Kim about the cryptic title, the concept, and the direction of her new work.

Over the past year, my head has been full of thoughts on how to make new works and how to organize my solo exhibition. Minoru Shimizu invited me to participate in the group exhibition showcase #6: “storytelling” (May 5-28, 2017, eN arts, Kyoto), and basically, it was a year when I focused on producing new works.

Story did take 10 years to complete if you include the planning and conception phase. For example, it is easy to talk about a “Girl With a Bear Head,” but taking a photograph of that takes time. It's a long process: making sketches, figuring out what the bear's face should look like, what the girl's body should look like. Then, after seeing the finished print, you look at it again and re-examine how you relate to it. Including this process of verifying whether I've produced what I envisioned, it took me a long time to finish things.

The new works are an extension of Story, and they're things I've been incubating for a long time. When I'm working, I myself have no idea of the order in which scenes or images emerge, the first scene might come first, or the last might. Anything is possible when we're talking about fantasy, the world of the imagination, but there are limits to what one person can do when taking photographs, and I do feel pressure in terms of what I'll be able to accomplish.

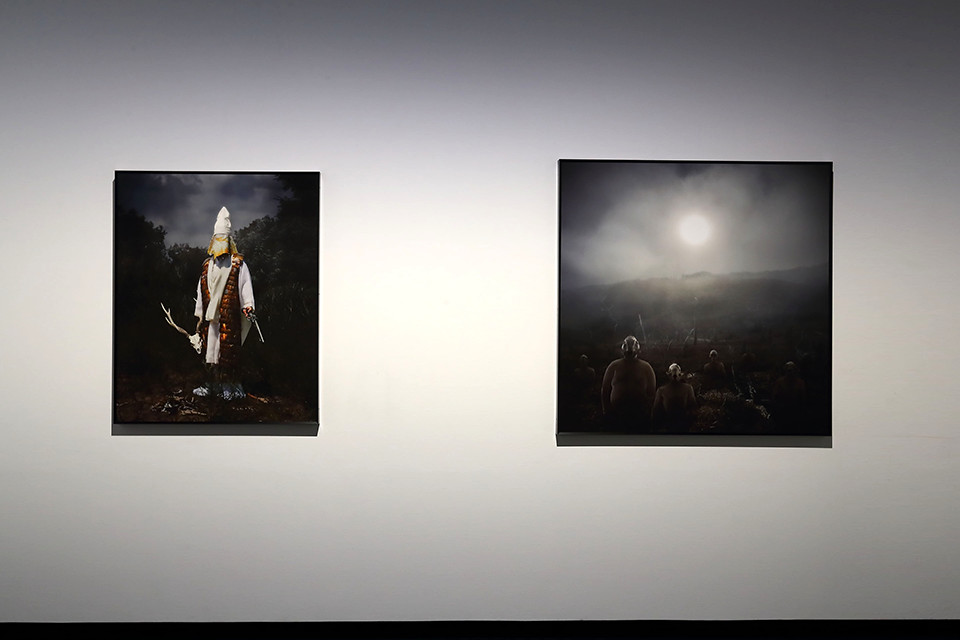

Girl With a Bear Head was the first work to take shape. There were things that I couldn't be sure about until I made it, but when I saw the print, I had a flash, like “That's it!” And I thought that I had to make this piece happen. In animism, or shamanism, animals are deified. That's something I can really relate to. I feel a deep connection to animals, and I think my ancestors must have been the same way. And when I was making Girl With a Bear Head, I learned that there is a Korean myth about a shape-shifting bear. In Japan there is the myth of Izanagi and Izanami, and similarly in Korea there is the creation myth of Tan-Gun. A tiger and a bear ask the gods to turn them into humans, and the gods make them undergo trials, saying they can become human if they succeed. Ultimately, the bear passes the test and becomes a woman. This bear marries a god who has become a human, and the king called Tan-Gun is born. I didn't know this story when I made the work, and I was very excited when I made the connection with this Korean myth, which explains my grandparents' origins.

Human genes evidently accumulate over many generations, but I felt this photo might lead to an unexpected place as I traced the roots of my ancestors. I think that producing a work of art makes you rediscover something, and I feel like I might unbind myself from something that confines me, relating to national borders and so on.

“Girl” from Story, (Grand Prize of the 39th public competition in 2016) © KIM SAJIK

Story is my own story. The new work features twin girls wearing red and blue outfits, and those girls represent the main character: me. When my parents told me “You are a Korean national, a Korean resident of Japan,” I learned that I have two names, a Japanese one and a Korean one. Doesn't that mean that when I was born, my mother also gave birth to another me with a different name? The twin is an expression of that. In the story, the twins grapple with reality and the conflicts of living in this world.

In the real world, if relations between Japan and Korea get worse, Korean people might have to leave Japan. But even if I go to Korea, I have no relatives and no place to live. I would be a kind of outcast. If that happens, I have no choice but to make my own place to go home to. The Story series deals with the desire to seek one's own homeland. Can my “twin” and I find the place we're looking for? I think that when this series is complete, it will lead me to the next group of works to make.

Pregnancy and childbirth are major events in women's lives. And men going off to war has been a recurring event throughout history. I present the symbolic image of a night with a full moon against this historical background of men and women, of humanity. I think a night with a full moon is when living things come into the fullness of their powers, both good and evil: new coral hatches, crime increases, and werewolves appear, though that is just a metaphor. Although it hasn't been proved scientifically, there is apparently data on record showing that earthquakes are more likely at the full moon.

About the pinecones, I had a dream before where a large pine tree spoke to me. It was a huge tree with a giant trunk, and it seemed important enough for me to do some research, which turned up all sorts of motifs. It is regarded as auspicious in Japan, and also as a sacred tree. After the Great East Japan Earthquake of March 2011, there was a lone pine tree that survived. It is a powerful symbol of vitality. Also, pine nuts are really nutritious, they're said to make you vigorous and women are advised to eat them during pregnancy and after childbirth. In shamanism, as well, they are presented as sacred offerings.

I envisioned pine nuts as little granules of life energy, like the eggs of coral. On a night with a full moon, a woman eats these granules of life energy that the pine tree drops in large quantities, representing the fertilization of eggs by sperm and the generation of life.

The work showing “men with animal skulls” represents men who died in war. Like the girl with the head of a bear, it is an image expressing how people and animals were originally one and the same, and I gave the men skulls of various different animals. All kinds of people are sent off to war, regardless of their physique or occupation. There are both herbivorous and carnivorous animals in this photograph.

In this exhibition, the photographs depict women as producing life and men as headed toward death, so I created a title with these associations.

It's great to read books about history, but you can grasp realities better if you actually see things or visit places yourself. For example, an old woman tells me about the war, about how her husband died and she gave birth and raised her child alone. When you see that child as an adult, or visit the house where the old woman has been living, you can sense and imagine all kinds of things. That kind of experience is really important, I think.

In a book by Shunsuke Tsurumi, I read that our modern sense of time, measured in minutes, is totally different from the days of the Old Testament. Tsurumi calls it “mythological time.” You might think that today we have no experience of mythological time, but actually we do, when we are young children who cannot yet read or write and we talk with our parents or other adults.

When a child hears from her mother that “leaves turn red in autumn,” the child starts telling people that leaves turn red in autumn as if they have known about it forever, even though they haven't. The origin of the story is the mother's words, but it grows beyond this and becomes the child's own narrative. This kind of narrative does not belong to anyone and is shared by everyone, in a way that is unique to the pre-literate. The book I read says that stories were handed down this in Old Testament days. You absorb stories, songs, movements and so on into yourself through experience, and then communicate them to others as if they were your own. I believe experience is important for my work because I think a perception of something like “mythological time” is crucial.

I'm shooting the Story series with careful attention paid to lighting. But the point of departure is snapshots. I think that photography is a medium that brings extremes together. When people ask for my opinions about photography, there are things that I cannot say because I do not understand yet, but I may be taking photographs precisely because I don't understand. You may look at a photograph and think you're seeing something you've never seen before, even though it shows specific things that are part of your experience. This is a very subjective thing, but it's a lot of what makes photography exciting for me. It is interesting to see if people can recognize a photograph as such when it shows things that are truly unknown

I am influenced by things in everyday life more than art, photography, movies and so forth. I'm talking about very trivial things that impress me, like the way people pray to the deity Jizo by the roadside, or a baby's instinct to nurse at its mother' breast. Most people are trying hard just to live day to day. Especially just after World War Ⅱ, so many people had nothing. But the way these people spoke and acted in this context means a lot to me, and it still has a lot to teach us today, I think.

One big thing that inspired me to submit work was the potential opportunity to show in Tokyo. I had wanted for a long time to exhibit work somewhere where lots of people would see it. Some of the judges were from overseas, and I was curious about how they would see the work.

One way that winning the prize changed me is that I had the chance to give a presentation. I usually only produce art, but this was a good opportunity to think deeply about the nature of presentation. Putting my relationship with photography into words was a big deal for me.

Yes, in many ways! I thought deeply, not about whether or not I win the Grand Prize, but about how to explain my work to people in words.

I feel that ways of seeing and experiencing the world differ from generation to generation. I would like to see photographs that show me new ways of thinking. Even if a photo is technically inept, I would like to see things that people believe in, things that make me say “Wow!”

Born in 1981 in Kyoto.

Solo exhibitions include Story (2015-2017, Art Space Niji, Kyoto) and the Busan Biennale Special Exhibition Asian Curatorial (2014, South Korea/Busan). Group exhibitions include showcase #6: "storytelling," curated by Minoru Shimizu (2017, eN arts/Kyoto) and Ascending Art Annual Vol.1: Shapes and Figures (2017, Spiral [Tokyo], Wacoal Studyhall Kyoto [Kyoto])

In 2018, Kim is scheduled to participate in the group exhibitions Selected Artist in Kyoto 2018: Kyoto Art for Tomorrow (Kyoto), Archiving the Archives at Mizunoki Museum of Art, Kameoka (Kyoto), and Artists' Fair Kyoto (Kyoto). Kim won the 2016 Grand Prize at the 39th New Cosmos of Photography competition.