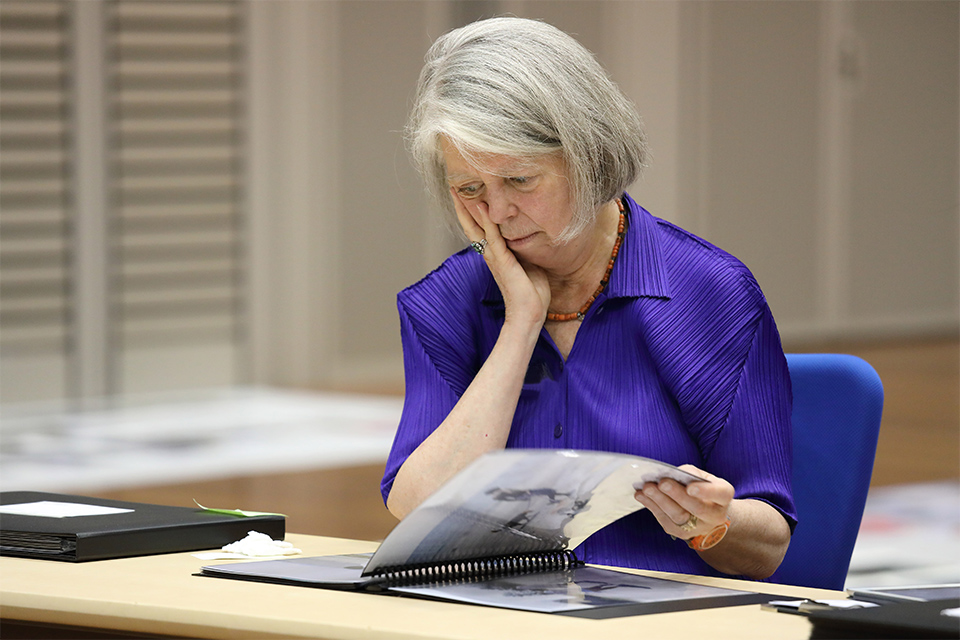

As the curator emerita of the SFMoMA Department of Photography, Sandra Phillips has been behind many important exhibitions, such as Crossing the Frontier: Photographs of the Developing West (1996) and Diane Arbus Revelations (2004).

She also directed the exhibition Daido Moriyama: Stray Dog (1999), a survey of the work of Daido Moriyama for a U.S. audience, which turned into a significant impetus raising the global reputation of Moriyama and many other Japanese photographers. Ms. Phillips has been devoted to becoming a leading researcher on Japanese photographer in the West.

We talked to her about her impressions of this year's New Cosmos of Photography judging, how Japanese photographers differ from the West, and her view of the future.

Everyone in my family was involved in art and the fine arts. My mother was an amateur photographer and took landscape photographs. I grew up in New York and often went to the Museum of Modern Art [MoMA] there. One time in high school when I went to MoMA, I found a sign near the door that said there would be a new gallery devoted to shining photographs in the museum. I thought what a wonderful and new idea !

I wanted to be an art history academic initially; I never pictured myself becoming a curator. I worked as an instructor while going to grad school, and after I received my Ph.D., I got a job at the university's arts facility because I couldn't find work in the area where I was living. But looking back now, I think it was very fortuitous that I took that job.

SFMoMA was founded in 1935, and it was the second modern art museum in the U.S. after MoMA. There were a lot of exchanges between MoMA and SFMoMA in the early days, and a structure developed while going back and forth between the two museums. That's the history of it.

The photography program has always been important to SFMoMA. The Department of Photography has been the biggest section of the museum for a very long time. In the early years, the Department of Photography's core collection was formed from the works of West Coast-based photographers like Ansel Adams, Edward Weston, Imogen Cunningham, Dorothea Lange, and others. San Francisco has become an enormously wealthy place economically very recently, but that was not the case in the past, and so the museum's budget was less generous. Photographic works were relatively inexpensive compared with paintings, which meant it was quite easy to acquire photographs on a limited budget. My predecessor was the one who started to collect Japanese photographs I think he timed the market well. As the global reputation of Japanese photographers has shot up, so too have the prices for their works, to the point where museums have difficulty acquiring them today.

Crossing the frontier : photographs of the developing West, 1849 to the present © SANDRA PHILLIPS

It was a huge event for us too. Moriyama is a magnificent photographer.

MoMA held an exhibition called New Japanese Photography in 1974 when I was living in New York. It was co-directed by John Szarkowski and Shoji Yamagishi, and it had a profound impact on me.

Later, when I started working at SFMoMA, the museum already held a few Japanese works in its photo collection because of the interest of my predecessor. So, it was very natural for me tocontinue his interest in Japanese photography.

Starting with New Japanese Photography, I saw a number of exhibitions in the U.S. featuring Japanese photographic works, and the works that especially grabbed my attention were by Daido Moriyama and Shomei Tomatsu. SFMoMA had already acquired some photos by Moriyama: for instance,we hadthe stray dog photo and the photo of sunbathing on the Zushi beach, and I wanted to further this collection. It become very clear to me that we also needed to do the Shomei Tomatsu exhibition.

Rineke Dijkstra: A Retrospective © SANDRA PHILLIPS

There's a distinct originality in Japanese photography. Especially photographs in the 1960s and 70s; they had a particular originality that set them apart from the U.S. and Europe. With all the globalization today, the individuality of each country is gradually fading. Nevertheless, you can still see something American in American photographers and something Japanese in Japan's photographers.

Shomei Tomatsu and others I researched were taking very critical photographs holding defiant and provocative views on the U.S. presence and its history with Japan. You could say that Japanese photographers are special in the way that society and history have a deep influence on photographic works made in Japan. I think this singular history informs the diversity and richness of expressions found in Japanese photography.

First of all, I would question whether heading overseas is really the best path, and I sense it would make matters all the more complicated in some respects. The U.S. and Europe have a culture of adorning walls with photographs, even if you're not that well off financially.

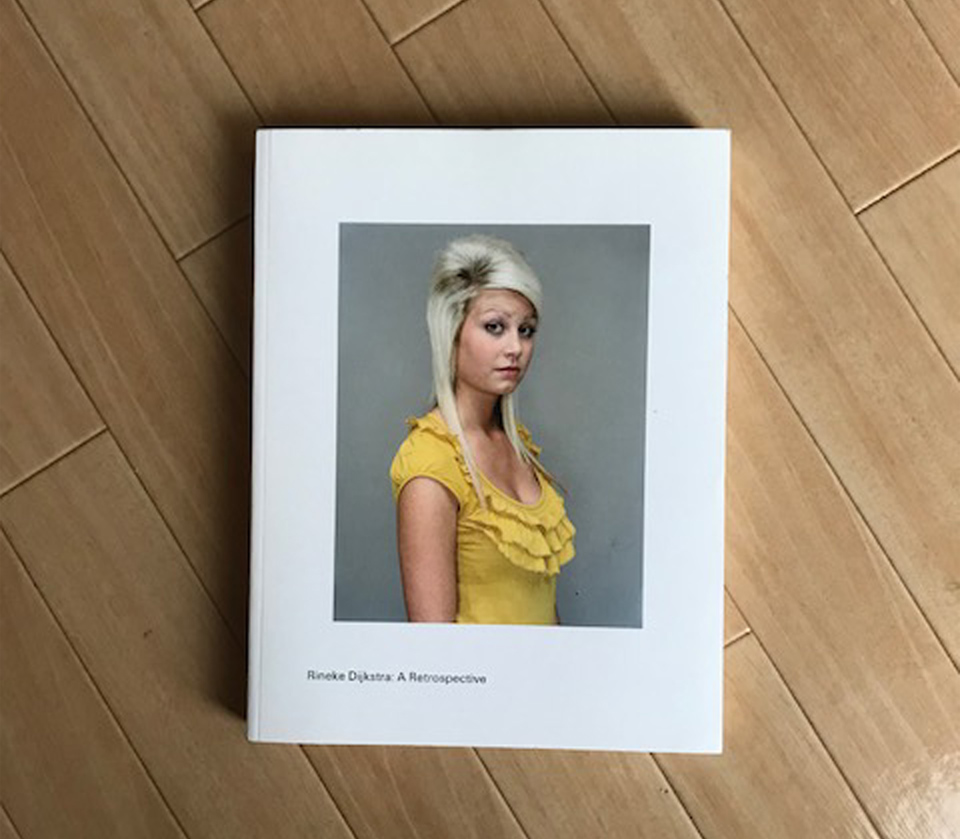

In Japan, however, amateur photography was the mainstream in the prewar era, and photography was not regarded as an art form until quite recently. Japanese photographers even now mostly choose to put out photobooks or publish in magazines to present their work. At art fairs, too, I often see young Japanese photographers' works in book form. The emphasis on producing photobooks is one big distinction of photographers in Japan. That's very sound businesswise, and they put a lot of energy into those activities. I think that's a key cultural difference.

When I interviewed Daido Moriyama, he brought some amazing photos he had taken for Provoke, a small-press magazine issued in the late 1960s. I told him I'd love to exhibit them at the museum where I was working, and I was shocked by his reply. He said, “In Japan, these are nothing more than photos you'd put out in the street like garbage for passers-by to help themselves to.”

I think it should be noted clearly that in Japan museums, galleries, and publishers exist first of all to provide that initial support to photographers.

Stephen Shore, : hc, First edition © SANDRA PHILLIPS

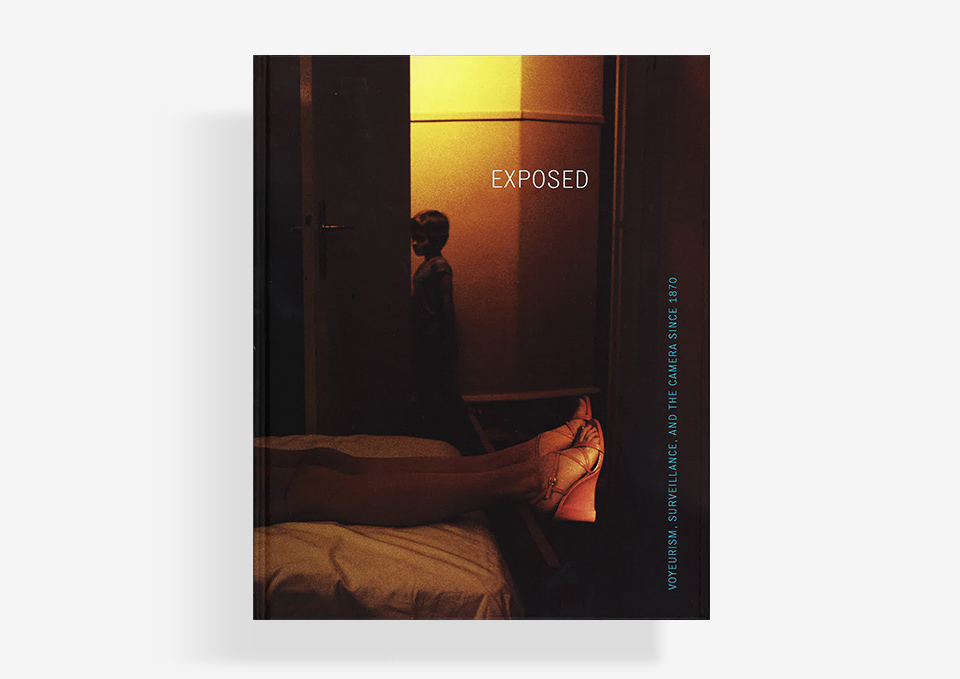

Exposed: Voyeurism, Surveillance, and the Camera Since 1870 © SANDRA PHILLIPS

The artist is the one who takes and conceptualizes photos and thinks about how the world should be seen. And I'm the person on the receiving end of the works. I try to grasp and understand the works as I receive them. That's why I don't make any assumptions or expectations about the subject matter of works I hope will materialize.

That's my job. My mission as a curator is to select, from an enormous amount of materials, things that deeply interest me and discover artists.

Personally, I want to see more photographic works taken in Africa and South America and other places not in the established photography circles like those in the U.S. and Europe. I don't think they have gotten sufficient recognition yet, despite how many amazing works there are in those places. And I will be pleasantly surprised if I can encounter deeply impressive works from Japan that I don't know about yet.

I'm planning a website to showcase Japanese photography. I'm thinking of including both Japanese and English text on the site, because I want Japanese people as well to understand more about the history, the richness, and the importance of photography in Japan as well as how much international interest there is in it.

I would like to tell them to be ambitious, because Japan has a wonderful culture of photography. Develop a rich imagination and take amazing photographs for the whole world to see.

Sandra S. Phillips is Curator Emerita of Photography at SFMoMA.

She has been with the museum since 1987, and assumed the position of Senior Curator in 1999. In 2017 she assumed the position of Curator Emerita. Phillips has organized numerous critically acclaimed exhibitions of modern and contemporary photography including Exposed: Voyeurism, Surveillance and the Camera Since 1870, Diane Arbus Revelations, Helen Levitt, Dorothea Lange: American Photographs, Daido Moriyama: Stray Dog, Crossing the Frontier: Photographs of the Developing West, Police Pictures: The Photograph as Evidence and An Uncertain Grace: Sebastiao Salgado. She holds degrees from the City University of New York (Ph.D.), Bryn Mawr College (M.A.), and Bard College (B.A.). Phillips was previously curator at the Vassar College Art Museum, and has taught at various institutions including the State University of New York, New Paltz; Parsons School of Design; San Francisco State University; and the San Francisco Art Institute. She was a Resident at the American Academy in Rome and received a grant from The Japan Foundation in 2000.