PRESENTATION

I'm interested in the subsistence of different people in the here and now. Subsistence means the act or condition of existing and maintaining a livelihood. I have created a range of works dealing with subsistence through our surrounding circumstances and through families, which is to say the communities to which we are all born and belong.

The Terada family, the subject of this work, have stored everything produced in the course of their daily lives. These included many different pieces and artworks created by the family members themselves. There were also diaries, letters, and other items that served as a record of their lives, which I borrowed for a time and photographed.

Norio, the father, swats mosquitoes each summer in front of their entranceway and keeps count of how many mosquitoes he kills every day, graphing the results. He keeps an accurate count, and his memo pad is crammed with strokes for each kill. He apparently tallied 4,033 mosquitoes over three years.

Shinichi, the grandfather, makes small curios and objects without any particular form or shape. When he completed a few, he would give them to the family, but it seems no one other than Shuko, the second oldest daughter, would take them.

In his diary, Shinichi wrote in great detail about his daily shopping, cleaning, and hobbies such as tinkering in the garden and playing gate ball, but he rarely mentioned his feelings. He wrote less and less in his later years, and his pen strokes became weaker. The days on which he wrote “I watched TV all day” grew more numerous, and the diary ends abruptly on Thursday, December 14, 2006.

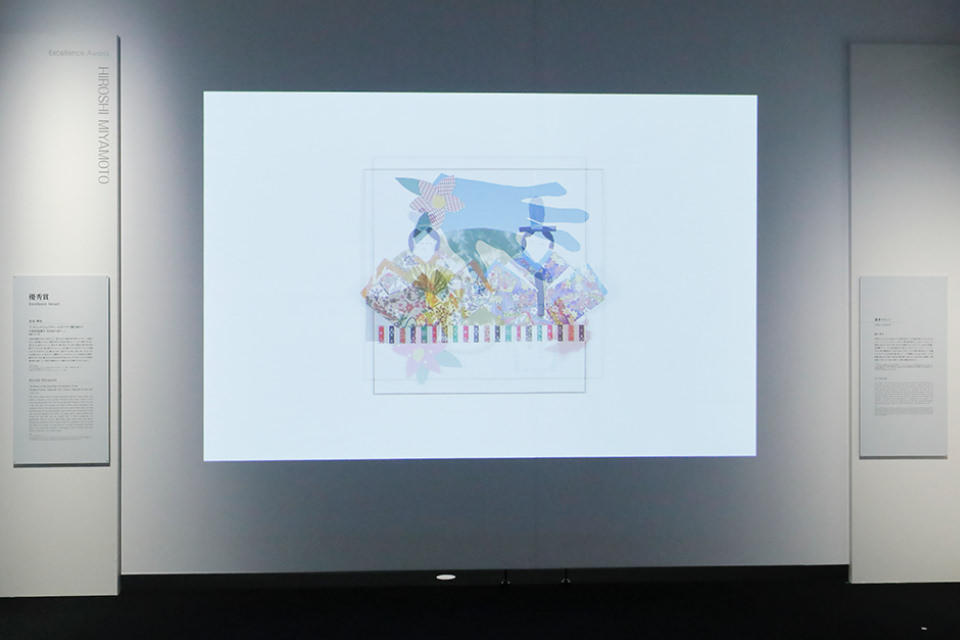

I photographed these items in an attempt to build an archive. I decided first of all to use a uniform format and size for the photos. I made the “height” of the photos — that is to say the shorter side of the photos — equal to 420 mm, which is the short side of an A2 print. This had the effect of making large objects look larger and small objects look smaller. My other objective was to take as many photos as possible. I placed each object in the center and blew dust with a blower while recording the object at three different exposures. I repeated this process over and over, taking 10,518 images. I allocated one photo per frame in the video, which was set to 30 frames per second.

The archive stores something like the memories of a family — in this case, the Terada family of Takatsuki City, Osaka. The memories are intended to trigger viewers, leading them to their own experiences and memories and prompting each person to reminisce. Reminiscing is something that emerges from individual interpretations and varies from person to person. I was looking for a range of interpretations from viewers, because I thought it's a good way to contemplate different means of subsistence.

I felt that 30 frames a second was very quick. I would have liked to have dwelled longer on each object. What was your thought process for choosing that speed?

(Miyamoto)

In a typical archive, by design the viewer first looks at the tag and then at the corresponding object. I thought that by forcing the viewer to watch the work in a fixed time frame, six minutes in this case, I could devise a way of viewing the work that is simultaneously both archival and non-archival. My objective was to have viewers remember their own history during the time they shared with the images.

Judges’s Comment

Noi Sawaragi (selector)

Families are enigmatic organizations. It's interesting that the Terada family keeps such detailed records and objects, but I believe every family, to some degree or another, has similar dormant stores of memorabilia and heirlooms. Most families, however, do not reveal these items, either because they are too personal or because they lack any significance for people outside the family. Or perhaps the objects have an inherent quality about them that makes people loathe to reveal them. Such objects are more private than personal information. So I'm curious how you established a relationship with the Terada family that allowed you to turn their family heirlooms into this collection.

(Miyamoto)

Shuko, the second oldest daughter, is an artist and we met at a gallery. At the closing of an exhibition, I became intrigued with the Terada family after hearing her family stories, and I suggested we hold an Terada family exhibition. We ended up exhibiting pieces made by the family in 2015, which was positively received by visitors and by the Terada family. This experience is probably why they agreed to my project. The fact that everyone in the family has a background in the arts or appreciates art helped as well.

(Sawaragi)

So the daughter with an interest in art was your entryway. Did you experience any objections while creating your work using the family's creations, like “We can't include this one” or “This is far enough”?

(Miyamoto)

The line between what I could show and what I couldn't varied a lot within the family. I visited the home once a month to borrow more items and return those I had photographed. When I asked whether I could borrow such and such next time, some people in the family handed them over right away while others hummed and hawed or avoided the subject altogether. I had promised to show them everything I had taken, so when they saw the photos they would sometimes object to showing certain things. Other times I would ask them for advice about whether I should show something. In other cases, they let me show something after erasing parts of the picture. So there were a number of patterns.