PRESENTATION

I conceived this work in the second half of 2015. At the time, Singapore and neighboring Malaysia were engulfed in a stagnant haze. The haze was caused by an increase in forest fires around palm oil plantations run by many companies. Farmers burned down forests to clear land to grow more crops.

According to Greenpeace International, tropical rainforest roughly the area of Singapore has been cleared for palm oil production in the last three years since 2016. That area is about 1,400 square kilometers — equivalent to clearing a forest the size of Metro Tokyo. What I found in my research that really shocked me was that haze has been affecting Singapore and Malaysia all the way back to the 1970s. The Singapore government started measuring haze levels and we could check the daily Pollutant Standards Index, or PSI, on the government's website starting in September 2015.

So what is in haze? And what does the air pollution index measure? The air pollution index put out by Singapore's National Environment Agency measures ozone, carbon monoxide, particulate matter — called PM10, and fine particulate matter — called PM2.5.

PM10 is found in the natural world. It is produced by the burning of trees and vegetation and is the main component of haze. PM2.5, on the other hand, is a much more worrying component as a pollutant. Exposure to PM2.5 is feared to cause various respiratory ailments. PM10 is particulate matter with a diameter between 2.5 and 10 micrometers, and PM2.5 is particulate matter with a diameter of 2.5 micrometers or less. So these are very tiny particles.

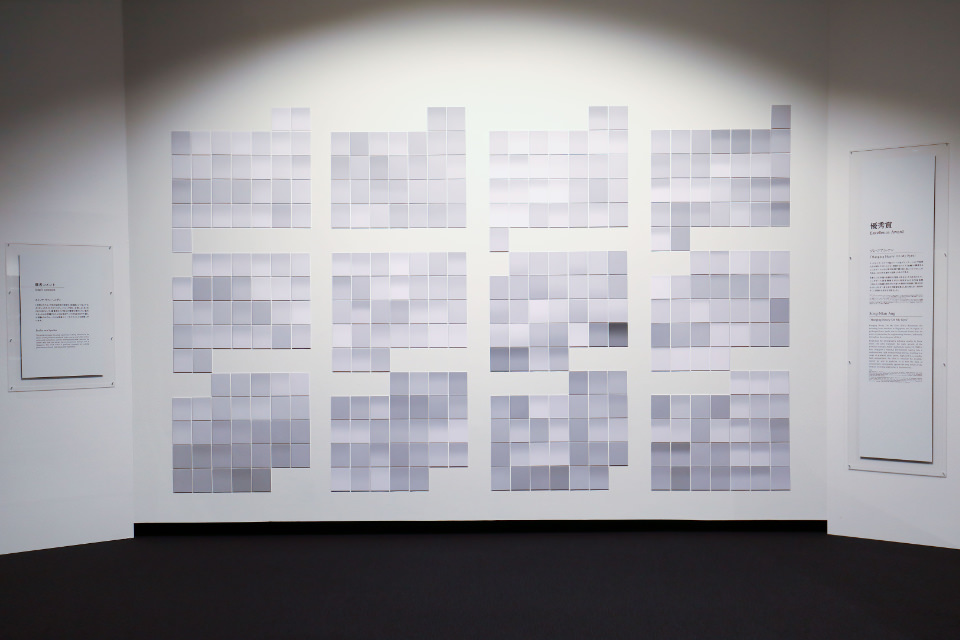

Many people who come to see my work ask: “Are those photos of haze in the atmosphere?” And some staff members who were involved in the production told me in the darkroom: “There's no story here.” The subject is haze, but I have treated it as something always out of sight. Haze even affects our impressions of sunlight. It has changed how we see things right in front of us.

Images are made up of three components: data, light, and time. Each print has two numbers on it. These are the maximum and minimum PSI values for the particular day. Every day for the entire year of 2016, I converted these numbers to an exposure time and converted that to a grayscale index. The 366 photos were created through long hours in the darkroom.

More than 170 years have passed since photographs came into the world, and over this time, major technological progress has been made. Photography has progressed from analog to digital, and more recently to video. Millions of images are created and consumed at a speed faster than we can see. But I deliberately decided to adopt a slow production process. It was my express intention to take my time, notice the finest details, and focus my attention on simple things people tend to overlook.

Singapore and Indonesia have had many talks on resolving the problem of haze. The Indonesian Vice-President said: “For 11 months, they [neighboring countries] enjoyed nice air from Indonesia and they never thanked us.” I would like to conclude with the words of Alan Moore: “Knowledge, like air, is vital to life. Like air, no one should be denied it.”

I think your book deserves to be seen. The book was executed exceptionally well. If at all possible, I think you should put the book on display beside the exhibit even if only for the rest of the exhibition.

Your intention with this work was to make use of the index-like character of photography. But since this work has no actual negatives, it is my understanding that the index you used is really a cause-and-effect relationship. Why did you decide to use photos when you had no negatives?

(Song-Nian Ang)

I have been trained in photography for a very long time. The way I make my work has evolved gradually over time, but I'm still undoubtedly a person in the medium of photography. There were no negatives because the only materials I had to work with were the numerical indices put out by the government. When I developed those numeric values on the photographic paper, there was nothing to interfere between the light source and the paper. That's why each print has such purity of form. I wanted the final form be the result of just data, light, and time alone.

Judges’s Comment

Emilia van Lynden (selector)

That was a great presentation. That explanation was a necessary part of your work.

Of the 1,992 works I looked at during this contest, why this one caught my fancy was its lack of anything you could call visual. We were surrounded by a sea of images all the time, and it took a lot of effort to assimilate them all. So when I saw your work, it gave me a sense of calm. And your book was especially good.

Environmental issues are a huge problem. I spent some time in Malaysia, so I know just how big the impact of haze is there. But people outside the region are not aware of the problem. Only when the haze gets really bad do newspapers and other media cover the story. The approach of an ordinary photographer would be to record the problem, but your approach is the exact opposite, which I found fascinating. I'd like more people to understand that you devoted a complete year to this project. It's an amazing piece of work.

About your exhibit, what was the reason for changing the format from the Singapore exhibit? Your book was magnificent, so why didn't you display the book with your exhibit?

(Song-Nian Ang)

I changed the exhibit format because of space limitations. I didn't display the book because the discussion about our exhibits talked only about the wall display. I would have liked to have put the book, or even a portion of it, on display in the space.